“When you get to the big leagues, you realize it really is a business and things happen that change your views.” – Johnny Bench

Far too often, conscious beings dwelling in human bodies struggle to find meaning in life. Can you blame them? We all enter a world, with no universal aims, operating on a three-dimensional game board, and are expected to maneuver around on the playing surface with a clear intention. We take our pawn, and shift it in various directions by way of the decisions we make, hoping that we are donned a winner. The problem is, there’s nothing in the rule book that defines a winner. Do you know why? Because there is no rule book.

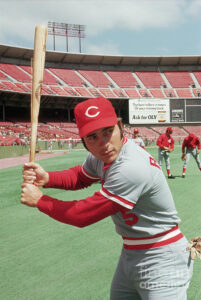

Due to these inconvenient circumstances, those who spawn onto the field of play are forced to figure it out as they go. As functioning beings with the ability to sense the space around them with precision, it’s on them to find their purpose. Every human is responsible for creating his or her own set of instructions. Once these guidelines are mapped out, the person can take deliberate action on the board as a means to achieve the end-goal that they scripted for themselves. The moment that target is hit, they can draw up a new one. Should a fella continue this process until their time runs out, chances are, independent of the actual results in their endeavors, they’ll be crowned a champion. Do you know why? Because if you’ve found what you want to do, and created objectives to pursue that are built around your overarching purpose, then you get to spend all of your waking hours, chasing what you want to chase. And what’s better than going after what you want? Nothing. So stay on your track, and you won’t lose. Fortunately for Cincinnati Reds legend, Johnny Bench, who many consider to be the greatest catcher of all-time, he knew at 6-years-old what his desired path would look like. With the encouragement from his dad, Ted Bench, a former semipro ballplayer in the late 1930s, who told his son in adolescence that “you can be a major league catcher,” the kid from Binger, OK hunted down his childhood dream, and accomplished more in the sport than the bulk of those lucky enough to take the field at the major league level.

The second Johnny was able to crouch down in a catcher’s stance, his father began teaching him the pivotal position behind the dish. Growing up in Binger, a small town of 600 people, about 50 miles southwest of Oklahoma City, Bench took full advantage of competing in an area that often times, due to it’s limited capacity, was short on ballplayers. Though his long-term goal was to become a big-league catcher, as a high schooler, Bench was a standout on the bump. “We only had 10 guys out for the team and one of those was a scorekeeper,” Bench recalled in a 1968 interview with The Cincinnati Enquirer. “We had to switch around a lot. I had a good fastball and a curve.”

Surprisingly, Binger’s lack of depth didn’t derail them from winning ballgames. That slim roster of 10 went on to win the state championship that season, with Bench leading the charge. On the mound, he didn’t lose a single start. He was so dominant that, throughout the entirety of his high school career, Bench only lost once. A game during his senior year in which he only allowed two hits, but, lost the contest on a pair of unearned runs. Away from the diamond, Bench also starred on the hardtop. “I had offers to go to Texas and most of the schools in Oklahoma on a basketball scholarship,” Bench said in that same interview. Yet, despite the success on the court, his original goal, the one he set out for as a child, never wavered. “I knew if I made it to the big leagues, it would have to be as a catcher because they needed them more, there was more opportunity. I just made it my object in life.”

In route towards this lofty objective, as a teenager, Bench would routinely take a 40-mile round trip to Anadarko, OK so that he could compete on the American Legion team there and showcase his skills against the premier talent in the area. It was there where the Cincinnati Reds signed him. An offer that included a small bonus, and a college scholarship, should he be interested in continuing his educational odyssey in the time he spent away from the field. Bench chose to throw all his eggs in one basket, which paid off faster than even he anticipated. After playing a few years in the minors across various levels, Bench got the call up to the big leagues at the ripe age of 19. In his first full season with the Reds, he won the National League Rookie of the Year. Two years later, he won his first of two NL MVP awards, leading the league in home runs (45) and RBI (148). To this date, no other player in MLB history has ever finished a year with that many homers while also catching at least 130 games over the course of the grueling season. When all was said and done, Bench, a first-ballot inductee into the Baseball Hall of Fame, finished his career with a pair of MVPs, 14 all-star appearances, 2 World Series rings, a World Series MVP, and an astounding 10 Gold Glove Awards for his uncanny ability behind the plate. His childhood dream had played out in an unimaginable manner that even the greatest dreamers of them all would have a hard time visualizing in their mind.

Putting aside his eye-popping statistics, upon getting his feet wet in the show, Bench quickly learned that there was much more involved surrounding his lifelong ambition than calling a good game, and hitting the ball in a space unoccupied by the opponent. After winning his aforementioned MVP following a jaw-dropping campaign, Bench endured a rare ‘down year’, for his standards, in the ensuing season. While he was still named to the All-Star team, won his 4th consecutive Gold Glove Award, and hit 27 home runs, Bench hit just .238, with a .299 on-base percentage, which was his worst mark as a starter across the entirety of his lengthy 17-year career. Not only did Bench have a hard time mimicking his astounding season, but his team went down with him. Cincinnati, who had won 102 games the year prior and made it all the way to the World Series before losing to Brooks Robinson and the Baltimore Orioles in five games, finished the 1971 year with a lousy record of 79-83.

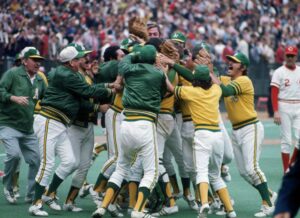

Before Bench could work towards getting back to his MVP form, he, along with the rest of the major leaguers, had to take care of some business off the field. Ahead of the 1972 season, a prior dispute between the players and ball club owners centered around pension benefits was unresolved by the time the regular season was supposed to begin. After August A. Busch, president of the St. Louis Cardinals said, regarding the matter at hand, that, the owners would not be contributing “another damn cent,” to the pension plan, the players, being the primary attraction within the product, leveraged their value. After player representatives held a 4-hour meeting with Marvin Miller, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, America’s Pastime experienced a ‘first’ that no individual attached to the game ever hoped to witness. In April of 1972, Major League Baseball endured its first-ever strike, after the players voted 47-0 in favor of holding out to get what they desired. It went on from April 1, to the 13th, and a total of 86 games were missed. Play resumed after the owners and players came to an agreement on a 500,000 uptick in pension fund payments. The cancelled games were never rescheduled, and as a result, no team played more than 156 games. Bench’s Reds played 154, and got back to their winning ways, finishing the year with a record of 95-59. Synonymous with ’70, Cincinnati won the National League pennant but came up just short in a hard-fought World Series against the Oakland Athletics (4-3). In the bottom of the 8th of the winner-take-all Game 7, with the Reds trailing 3-1, Bench had a chance to flip the script. With only one out in the inning, and runners on 2nd and third, Bench entered the batter’s box. In the past, Oakland Athletics manager, Dick Williams, had said, in reference to this very situation, that he would never deliberately allow the winning run a free base via an intentional walk. Sadly, for the fans of the Big Red Machine, Williams backtracked on his word. “It’s true I said I would never walk the winning run,” Williams stated after the series clinching victory. “But I can qualify that I also will not let Johnny Bench beat me with his bat. I did that today only because it was Johnny Bench at the plate.” After Bench was given the free base, his teammate, Tony Perez, knocked in Pete Rose in a sacrifice fly, making it a one-run game. Unfortunately, Oakland’s Rollie Fingers got Denis Menke to fly out and end the inning. Fingers proceeded to close it out in the 9th, giving the A’s their 6th World Series title. Though The Fall Classic ended in utter disappointment, Bench had gotten his game back on track. During the regular season, he hit 40 home runs and had 125 RBI, leading the league in both categories. For his stellar performance, Bench received his 2nd NL MVP award.

Since the game of baseball had been around for well-over half a century with no work stoppages, one would think that the offbeat start to the 1972 season was a mere fluke. A bizarre lock-out that would surely be forgotten in no time. If one was a betting man who only places safe wagers that are in favor of the odds, then, based on history, a smart move for him to make would be to gamble that there wouldn’t be a sit-down strike for at least 20 more years. 20 being a conservative amount, given the elongated stretch where the nation was used to watching impediment-free seasons play out. Yet, just like with any sports bet, the odds can be deceiving. The very next year, an owner-induced lockout took place in February, 1973. In addition to the increase in pensions, the aftermath from the 1972 strike also included the addition of salary arbitration to the collective bargaining agreement (CBA). This amendment allowed players who, prior to becoming eligible for free agency, could receive a boost in pay in accordance with the present market, and their personal performance. So if a player was outperforming his contract, and had the numbers to prove it, he could file for salary arbitration, and grant himself a shot at earning some extra dough if successful in the act. After this money-based alteration was added to the CBA in 1972, the deal expired the following year. Its expiration influenced the owners to request that the arbitration process be defined with more transparency in the new agreement. The lockout began on February 8th, and was thankfully put to rest on February 25th after the parties came to a consensus regarding on the verbiage of the proceeding. Unlike the year prior, since business was handled at the top of the calendar year, no regular season games were cancelled. Though they were forced to postpone the start of spring training. Something they would do yet again in 1976 when the game underwent it’s third stoppage. This break-in-the-action was inspired by the 1972 court case, Flood v. Kuhn. In October 1969, Curt Flood, All-Star centerfielder for the St. Louis Cardinals, was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. Upon hearing that he had been dealt after serving 12 years with the Red Birds, Flood flabbergasted the parties involves by announcing his retirement from professional baseball. From his vantage point, the trade was a ‘shocking’ move, a decision that aggrieved him, due to the extensive time he had spent with the Cardinals. In a statement made after the exchange, Flood said, “When you spend 12 years with one club, you develop strong ties with your teammates and the fans who have supported your efforts over a period of years.” He then went on to cite that the decision to step away from the game was due to his perceived physical decline, though only 32, and his desire to dedicate more time and energy into his private business interests. Had he been younger, then Flood, per his sentiments, would have enjoyed playing for the Philadelphia Phillies. Since his decision to quit came out of left field, it was clear that there was much more to his rash reaction.

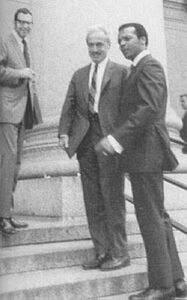

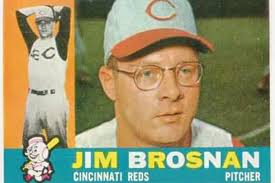

Following the trade, Flood put in a request to Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner of baseball at the time, that he be authorized to handle his 1970 contract as a free agent, as he believed it was his right to explore the market, as opposed to being tied down to a club, just because it was time for a contract renewal. As expected, Kuhn denied his ask. In response, Flood pulled the plug on his retirement, and filed a lawsuit against the league, vituperating baseball’s reserve clause. For those unfamiliar with the term, the reserve clause was a stipulation in a player’s contract that granted team’s the right to reserve a player until he was traded, sold, or released. In his objection, Flood claimed that MLB was a monopoly functioning in limitation of trade. “The baseball establishment maintains a lifetime grip on any player who wishes to play professional baseball in the United States,” he said at the time when questioning the league’s degree of control. With the reserve clause having been tried twice prior in the Supreme Court, and each time upheld as it was recognized as a sport, and not inter-state commerce, Commissioner Kuhn did not back down, and the case was birthed. In court, a representative on Flood’s side bracketed the traded player as a “high-priced slave”. Among those also testifying on Flood’s behalf was Jackie Robinson, Hank Greenberg, and Jim Brosnan, a trio of former ballplayers. In the case of Robinson, the iconic ballplayer was far too familiar with what Flood was going through. In 1956, the Brooklyn Dodgers, the team the Jackie played on for 10 years, a franchise who, with the help of tremendous play, won six National League pennants, the 1955 World Series, and finished with a winning-record each year he starred for them, wound up trading him to the struggling New York Giants. A team that had just finished 20 games below .500, despite having just won the World Series in ’54, and were led by arguably the best player in the league at the time, Willie Mays. Rather than suit up for New York, Brooklyn’s rival, Robinson reacted like Flood, and opted to retire. A decision he stuck to.

The primary focus from Flood’s team was to create a more coherent, less confined, system to counteract the perceived divergence between the owners and players. According to a report published by The Shreveport Journal surrounding the matter, Flood and Co.’s primary provision was to create a “clause that, instead of containing an option on a player’s service for life, reduces it to a specific number of years,” so that the player, following the end of that period, can be “given an opportunity to establish his market value by obtaining bids from other clubs.” To which the owners denounced, claiming that “it would cost the club that originally signed the player the money it had spent in training the player,” while also mentioning that “under that provision all talent would gravitate to the wealthiest clubs.” In defense of Flood, Jackie Robinson, when referring the reserve clause, called the distinct article listed in contracts, “one-sided”, and that “anything one-sided in this country is wrong.” Greenberg echoed the flaws within the clause, pushing for a particular amount of years for a team to retain control over a player, as opposed to possessing that player for the entirety of their career. The power-hitting Detroit Tigers legend felt that the reserve clause, as it stood, was “obsolete and antiquated,” and deemed it a “unilateral contract in which the player has no choice but to accept terms because he can’t play elsewhere. It’s very difficult for the average player to discuss contract terms when he can’t go anywhere else.”

Jim Brosnan, whose career was not nearly as decorated as Robinson’s nor Greenberg’s, was brought on to discuss the imperfect structure of the reserve clause from the vantage point of your average ballplayer. It was here where people were able to get a firsthand feel for the absurdities within the documentation. Though he pitched nine years in the bigs, primarily as a reliever for the Reds, Cubs, Cardinals, and White Sox, Brosnan was more well known for authoring a 1960 memoir, titled The Long Season: The Classic Inside Account of a Baseball Year, 1959, than his actual play on the bump. As a ballplayer stunt doubling as an author, Brosnan recalled a handful of examples in which he was told by Bill DeWitt, the Cincinnati Reds General Manager at the time when he played for the club, that per a stipulation in his contract, he was prohibited from publishing any of his work during the season without prior permission from the team. This came as a shock to Brosnan, as he had never noticed that provision before when analyzing his agreement. Aside from pointing out abnormalities within contracts to further push for refinements, Brosnan also brought some humor to the situation. When talking about his 1954 year in professional baseball, a season where he see-sawed levels with five different teams, Brosnan mentioned that at one point amidst his erratic, travel-heavy season, his wife threatened to divorce him. According to an article in The Times, in his testimony, Brosnan spoke on his wife’s annoyance with the constant need to relocate to follow of his goal of becoming a big leaguer. “Once when I got called to move, she had just bought two weeks of steak for the freezer. She wanted to know what to do with the steaks.” While the man referred to by his teammates as “Professor” wasn’t what you’d deem as a ‘lights-out’ reliever, there was no denying that his wry wit, and clear-eyed frankness, lit up any room that he spoke in.

While the case was playing out, Flood had decided to sit out the 1970 season. Ultimately, him and his team fell short at the trial, but held on faith when it was time for appeals. In 1971, Flood returned to baseball, singing with the Washington Senators, a deal that, if honored, guaranteed that his decision to sign with the ball cub did not compromise his ongoing case. Unfortunately, Flood underperformed, and after just 13 games where he hit .200, left the organization. It would be the last time Flood suited up for a major league team.

In June of ’72, Flood’s appeal was unsuccessful, as the Supreme Court ruled in baseball’s favor. Though him and his team were defeated, the contradicting language used by the Court in their decision didn’t close the door entirely on the matter. In 1975, when a pair of pitchers, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally fought for their right for free agency, similar to Flood, a different outcome arose in the court of law. Known as the Seitz decision, on December 23, 1975, arbitrator Peter Seitz avowed that MLB players would become free agents after serving only one year for their team. Their previous contract would now be defunct, which abolished the reserve clause, and birthed free agency. In essence, Flood served as the valiant martyr to fight for what was right for his associates. Though the new rule was of no benefit to his career, his actions revolutionized the course of negotiations forever.