The 1994 San Diego Padres, as a unit, did not have much to write home about. At the time of the strike, their record was an abysmal 47-70, a mark that ranked them dead last in baseball. Yet, even though their house was dark, appearing to lack electrical power, a lone light shined bright in the living room. The sector in the abode considered to be the “main attraction” possessed an illumined glow that made San Diego fans forget about the gloom. In their last game before the season was stalled, San Diego Padres star right fielder Tony Gwynn collected three hits against the Houston Astros, which raised his league-high batting average to an astounding .394.

Dating back to the Fourth of July in 1993, Gwynn, in a sample size of 164 games, was hitting .400. In other words, the two-sport standout athlete at San Diego State had been on fire for quite some time and did not appear to show any signs of cooling down. The baseball world had not seen a player finish a year with an average at or above the illustrious .400 mark since Ted Williams hit .406 in 1941, so watching a player who was in and around it this late in the year get the rug pulled out from under him was devastating. “I’m not even going to think about it,” said Gwynn, when asked in mid-August of 1994 about his potential feat being put on pause, “but I don’t know how I’m going to keep it going. I plan on hitting off the tee during the strike, but I don’t know who in the world is going to be throwing to me” (Johnson 5).

Tony Gwynn was not the only MLB superstar performing at a supernatural pace when the season was put to a stop. Chicago White Sox standout Frank Thomas, the AL MVP in 1993, carried his dominating ways into the 1994 season by slugging .729, with an on-base percentage of .487. Both marks put him atop the charts in their respective categories. Had the season continued to transpire, “The Big Hurt” would have had a real shot at making history and penciling his name alongside two of the best to ever do it. At that point in Major League Baseball history, the only other qualified players to end a year with a slugging percentage north of .700 and an on-base percentage of at least .500 were Ted Williams (1941, 1957) and Babe Ruth (1920, 1921, 1923, 1924, 1926). Since the season was cut short, Thomas was not given the chance to raise his OBP, keeping him on the outside looking in when it came to etching his name alongside the “Splendid Splinter” and “The Sultan of Swat.”

However, as the years rolled on, a player who did end up qualifying for the rare group was Barry Bonds, who accomplished this remarkable achievement in four consecutive seasons (2001-2004). Oddly enough, Bonds, in the strike-shortened 1994 year, was on pace to become just the second player in MLB history, the other being Jose Canseco (1988), to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases over the course of a single season. In 112 games during his 1994 campaign, Bonds had already clubbed 37 home runs and swiped 29 bags, so his entering the 40-40 club seemed inevitable. No need to throw a pity party for the great, though, as Bonds wound up hitting 42 home runs and stole 40 bases in 1996.

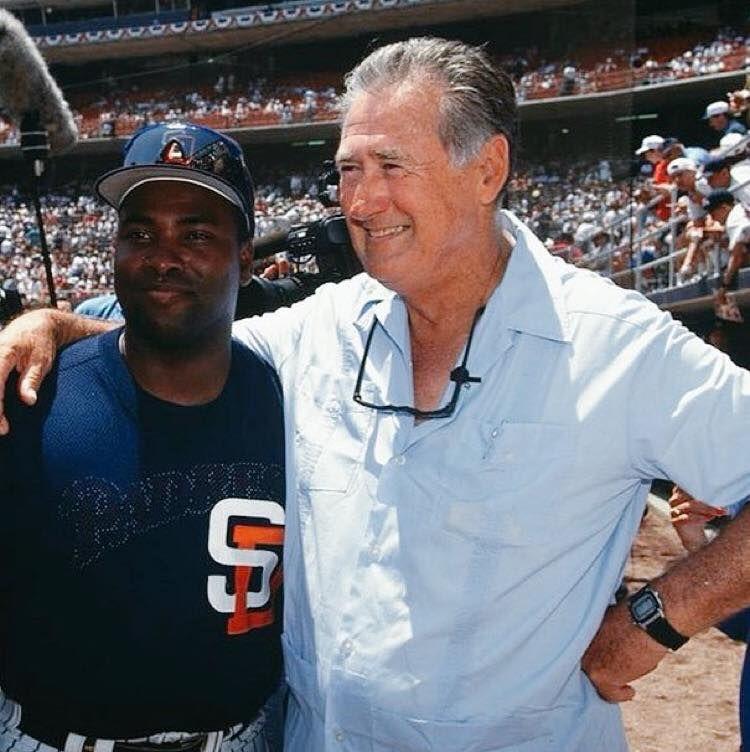

At the time of the strike, with a third of the season left, Bonds was one of six players—Matt Williams, Jeff Bagwell, Ken Griffey Jr., Frank Thomas, and Albert Belle being the others—to have hit at least 35 home runs. Williams, Bonds’s teammate on the San Francisco Giants, had a league-high 43 long balls, which meant he had a real shot at cracking 60, something that had not been done since 1961 when Roger Maris hit 61. Comparing their clips, both Maris and Williams each had 43 home runs through their team’s first 115 contests, so it was safe to assume that Williams could have possibly reached 60 or at least surpassed Hack Wilson, who hit 56 home runs as a member of the Chicago Cubs in 1930, which, at the time, was the record for most homers in a single year by a player in National League history.

In addition, there had never been a season in baseball’s rich past in which more than one player hit 50 or more home runs, and if there was ever a year where it felt like a real possibility, it was 1994. “It’s fun, what’s been happening this year,” said Barry Bonds in a published article written by American sportswriter Gordon Edes that referenced the noteworthy performances on display across the league. “A lot of guys could knock in 100 runs, maybe three guys in the American League could wind up with 50-plus homers. Look at the year Matty (Williams) is having, the year Jeff Bagwell (104 R, 39 HR, 116 RBI) is having” (Edes 7). “It’s like damn, you wish this strike wasn’t coming right now. They keep saying there are things only Babe Ruth could do, and now you’re seeing six, seven players who have a chance to do the same thing.”

While there was a fair share of hitters with mystic-like pop at the plate, there was a notable name on the mound that was also operating at a historic rate. Atlanta’s Greg Maddux, the Cy Young Award winner in the last two seasons and eventually for 1994 and 1995, making it four in a row, posted a 1.56 earned run average with a WHIP of 0.896 in 202 innings of work. In the Live Ball Era (1920-), only one other pitcher finished a year, while logging at least 200 innings, with an ERA under 1.60 and a WHIP below .9. That hurler was, of course, Bob Gibson, who exceeded these marks in 1968 while carrying out arguably the greatest pitching season of the century.

When speaking after his final start (a complete-game, three-hit shutout win over the Colorado Rockies) of the 1994 year, Maddux, in summary of his incredible stretch, said, “This is the best 4 ½ months I’ve ever had” (Miller 9). Rockies manager Don Baylor, whose team just got blanked by the legendary right-hander, said of Maddux: “He’s a treat to watch. I don’t know if we had one good swing” (Miller 10). For modern standards, having eclipsed the 200-inning mark, Maddux had already logged what many would consider to be a “full season” of statistics. Yet, because of his sheer imperium, start after start, the universe missed out on the possibility of seeing an even more epic compilation of numbers, had Maddux been given the chance to continue pitching through the end of the year.

Though lowering his ERA down to Gibson’s inconceivable 1.12, the MLB record for all qualified pitchers during the Live Ball Era, seemed to be out of the cards—no pun intended while referencing the St. Louis Cardinals legend—it would have been interesting to see what Maddux could have ended with. Though the two differed in style, as Gibson possessed a fearsome, ferocious-like delivery with high speed on his fastballs, whereas Maddux was more known for his ability to leverage his uncanny command in an effort to outsmart the opposition, the pair of aces did share one pivotal trait, which was their immutable desire to compete. On the rare occasion that Maddux misplaced a ball that he threw, spectators watching him perform would often see “The Professor” shout out a profanity or two to himself as a way to evince his burning passion for his profession.

If you put his incredulous numbers aside, Bob Gibson, off his sinister-like glare alone—the expression he would frequently have across his face while mowing down the hitters—would still be in consideration for most intimidating pitcher of all time. After wrapping up his illustrious regular season in 1968, Gibson and his teammates spent the next few days in preparation for their World Series matchup against the Detroit Tigers. During this interval, Milton Gross, author and sportswriter, caught up with the St. Louis Cardinals to get a feel for where their collective energy lay ahead of the Fall Classic.

In a published article in the Omaha World-Herald, Gross penned an interaction he was privy to between Gibson and his teammate, the great Lou Brock. Brock had asked Gibson if he would be receiving a new car for his incredible pitching season, as he had heard that Denny McLain, the ace on the Tigers, who, like Gibson, had a tremendous year, had been gifted a snazzy ride for his contributions. Gibson responded by questioning his statement: “What new car?” To which Brock replied, “You mean nobody’s giving you one? I see they just gave McLain a ’69 Thunderbird.” Gibson, staying true to his fierce ways, said, “Nobody gives me anything but a hard time” (Gross 12).

Later in the article, Gross talked about his examination of Gibson’s personal locker. Populating over his compartment were a set of buttons and a toy tiger that was taped to the shelf by its tail—the tiger doll in reference to the impending opponent. Written on one of the buttons was the phrase, “I’m not prejudiced. I hate everybody.” Also on the scene was a graphic sign that read, “Here comes da judge”—an idiom that one could infer to be in reference to Gibson’s supernatural ability to hold court over the opposition. As is believed, the body adheres to the direction of the mind, and it appears that Gibson knew how to correlate this connection better than most—scripting out the person he wanted to be and seeing his truths on the regular, so that the body would follow suit with ease when it was time to battle.

Works Cited

Edes, Gordon. “Bonds Reflects on 1994 Season.” Sports Illustrated, 10 Aug. 1994, p. 7.

Gross, Milton. “Gibson Prepares for ’68 World Series.” Omaha World-Herald, 30 Sept. 1968, p. 12.

Johnson, Mark. “Gwynn Faces Strike Uncertainty.” San Diego Union-Tribune, 15 Aug. 1994, p. 5.

Miller, James. “Maddux Shines in Final ’94 Start.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 8 Aug. 1994, pp. 9-10.