For those unaware, players, three times, in three straight off-seasons (1985, 1986, 1987), filed grievances against the owners for collusion. After the 1985 season, during the free-agency period, 28 players signed new deals, but only two of them joined new teams. The players, rightfully so, perceived this as “fishy” behavior and proceeded to charge the owners with acts of collusion (later dubbed Collusion I).

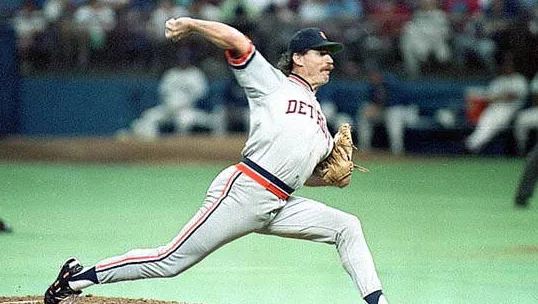

The very next off-season, more suspicious action transpired, prompting the MLBPA to file another collusion grievance (Collusion II). This complaint was centered around the owners seemingly obstructing the movement of marquee free agents, while also carrying their shady behavior into the talks with players who had filed for arbitration. At this point in time, the last big-name player to ink a deal with a new organization in free agency was Bruce Sutter, eventual Hall of Fame pitcher, who joined the Atlanta Braves in December 1984. In 1985, Detroit Tigers outfielder Kirk Gibson, playing in his age-28 season, batted .287, hit 29 home runs, and finished in the top 20 in AL MVP voting. Eager to capitalize on his standout season as he headed into free agency, Gibson was taken aback when his agent informed him that none of the owners around the league were interested in acquiring him. Due to this mysterious behavior, Gibson was then forced to re-sign with Detroit at a time when his present-day statistics and potential future output quite clearly warranted him a sizable deal on the market.

So when the off-season of 1986 rolled around, and star free agents like Tim Raines, Andre Dawson, Jack Morris, Lance Parrish, Bob Horner, and Rich Gedman were getting the “Gibson” treatment when speaking to other teams, while the few fortunate enough to switch teams did so while taking a pay cut, the grievance was filed. In January 1987, the MLBPA filed their third collusion grievance in as many years (Collusion III), citing that the owners were, yet again, machinating to suppress the market. “It’s become obvious to us that they’re orchestrating prices,” said Gene Orza, associate general counsel of the MLBPA, in the Arizona Republic when speaking on the owners’ now consistently suspicious decisions when in talks with free agents. “When there’s interest in teams, it’s remarkably similar” (Smith 8).

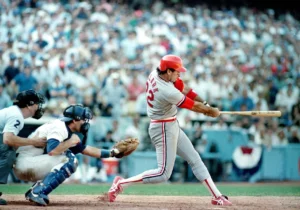

The alleged “price-fixing” by the owners was pointed out by the players’ union with another real-life example of a ballplayer who fell victim to the supposed collusion. In 1987, St. Louis Cardinals 1B/OF Jack Clark had the best offensive year of his life. He hit a career-high 35 home runs and led the league in five separate offensive categories (BB, OBP, SLG, OPS, OPS+). Clark finished third in NL MVP voting, right behind the winner Andre Dawson and his own teammate, the great Ozzie Smith. Like Gibson, Clark had his sights set on a nice payday. Though he was able to ink a deal with a new ball club, as he signed on with the New York Yankees, Clark, in the process of doing so, took $100,000 less per year in guaranteed money. “Collusion is price-fixing, not location-fixing,” said Orza when speaking on the problem at hand being the money, and not so much the player’s inability to find a new team, which was more significant an issue in prior years. “Collusion takes different shapes. . . . Sure, Jack Clark moved. But he moved at a price that was fixed. Clubs are making offers, but they’re all making the same offer” (Smith 9).

In raising their voices and escalating the matter to the courts, the players went a perfect three-for-three in their collusion cases. With all three accounts, the owners were found guilty of colluding to impede player movement, a direct violation of the CBA. As a result, reparations were paid out to the players who were affected. Along with a sum of cash, the arbitrator involved with the first collusion case, Thomas Roberts, at the top of 1988, granted seven impacted players the option to become free agents once again. One of them was, of course, Kirk Gibson, who proceeded to leave the Detroit Tigers and sign with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

As many know, in the World Series of that same year, Gibson hit one of the most memorable home runs in major-league baseball history—a pinch-hit, walk-off blast, down to his last strike, with two outs in the ninth inning of Game 1 off Oakland Athletics star Dennis Eckersley. As he rounded the bases, Gibson, limping through injuries to his legs, knees, and hamstrings—the string of impairments that originally kept him out of the starting lineup—blocked out the pain for a brief moment and pumped his fist in celebratory fashion. Just hours before the game, Gibson was unable to jog across his living-room floor. He had not seen any live pitching in days. Yet, as they say, when there is a will, there is a way. The swing has been immortalized, but not enough credit goes to Roberts, the arbitrator who allowed Gibson to retest the waters. Without Roberts, we may very well have missed out on bearing witness to one of the most iconic moments in not just baseball history, but sports history.

After Roberts set the standard, the arbitrators in the ensuing cases followed suit. In 1989, arbitrator George Nicolau settled upon a stable amount of funds to dish out to the impacted players and, like Roberts, allowed them to get a fresh look in free agency. The same outcome transpired in Collusion III. As touched upon earlier, at the end of the lockout in 1990, details surrounding the ongoing collusion problems were brought to the table, and in November 1990, Jack Clark and 15 other impacted players received a portion of a $280 million settlement from their court win over the owners. In addition, they too became “new-look” free agents.

One of those 15 players was the great Jack Morris, who left the Detroit Tigers and ended up signing with the Minnesota Twins that December. Akin to Gibson, Morris put on a performance for the ages in his first year with his new ball club. In 1991, the Minnesota Twins reached the World Series after missing the playoffs for three consecutive seasons. In the AL Championship Series, Minnesota rolled over the Toronto Blue Jays, winning the series 4-1, and were to square off against the Atlanta Braves in the Fall Classic.

In Game 1 of the World Series, Morris set the tone for Minnesota, as the veteran hurler threw seven strong innings and allowed just two runs in a win. The Twins would go on to take the next game as well but proceeded to lose the ensuing three contests. After Kirby Puckett hit a walk-off home run in the 11th inning of Game 6 to keep Minnesota alive, the Twins handed the ball back to Morris for the winner-take-all contest. Though Morris had just thrown six quality innings in Game 4, on top of the work he had compiled in the series opener, Minnesota felt confident in their star pitcher, fatigued or not. “This is how we set it up, to have him pitch three times,” said Twins manager Tom Kelly, after announcing that his 36-year-old would get the nod for the winner-take-all contest. “I’m very, very confident he will pitch the best he can. Whatever he does tomorrow is going to be good enough for me because he’s carried more than his share” (Blum 10). When asked about the golden opportunity, Morris, in an article published by Ronald Blum, AP Sports Writer, was quoted saying, “I don’t know any pitcher who hasn’t dreamed of pitching a game like this.” In that same piece, Morris reminisced on his childhood and recalled role-playing this exact situation with his brother, back in the day when they competed against each other in a friendly game of Wiffle Ball. “He used to be Mickey Mantle. I used to be Bob Gibson” (Blum 11).

In Game 7, Morris did his best impression of the legendary St. Louis Cardinals pitcher, and then some. With everything on the line, Morris seized the moment. In the high-stakes, sink-or-swim showdown, Jack Morris became the first and only pitcher in World Series history to throw ten shutout innings in a Game 7. While it was not pretty, as Morris found himself in multiple jams throughout the contest, the seasoned vet leveraged his experience and put on a performance for the ages. With the game still tied at zero heading into the ninth, Morris, after a shaky eighth, pitched a clean 1-2-3 inning. “I told him after the ninth, ‘That’s enough Jack,’” said Kelly in recollection of the conversation he had with Morris after the hurler blanked the Braves through regulation (Blum 12). Morris, being the fiery competitor that he is, responded, “TK (Tom Kelly), I’m fine. I’m fine.” Kelly, remaining adamant on replacing his starter for a fresh arm, told Morris, “You did enough. It’s time for the boys to carry some of the load,” to which Morris fired back with, “TK, I’m fine. I’m REALLY fine.” Morris’s level of self-belief trumped Kelly’s idea, as the manager decided to keep him in the ballgame.

As luck would have it, Morris pitched another 1-2-3 inning in the tenth, and in the bottom of the inning, his teammate Gene Larkin hit a walk-off single to give the Twins their third World Series title in franchise history. “It still hasn’t sunk in yet,” Morris, the obvious choice for World Series MVP, said just 20 minutes after the 1-0 win to seize the championship. “I’m sure it will someday” (Blum 13).

Works Cited

Blum, Ronald. “Morris Shines in Game 7 Glory.” Associated Press, 28 Oct. 1991, pp. 10-13.

Smith, John. “MLBPA Alleges Collusion in Free Agency.” Arizona Republic, 15 Jan. 1987, pp. 8-9.