To the plurality of boys growing up in America in the 50s and 60s with an interest in athletics, Mickey Mantle was much more than just a fantastic ballplayer. He was a national icon who represented the American dream in a mythological-like manner—a folk hero with Paul Bunyan-like characteristics. Akin to Bunyan, “The Mick” showcased strength and vitality in his profession, while carrying out a career that was more chimeric in its nature than it was concrete. He grew up in Commerce, Oklahoma, a small town of less than 3,000. His father, Mutt, named him after the Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane, whose government name, funny enough, was Gordon Stanley Cochrane. Nonetheless, Mutt was set on honoring the ballplayer’s nickname a full two years prior to Mickey’s birth. With that said, even prior to him spawning into this universe, Mickey Mantle was destined to be a ballplayer. “He’s just a plain, big old country boy who liked to play baseball from the day he was old enough to carry a mitt,” said Ralph Sears, the bank president in Mickey’s hometown, via a 1956 newspaper article written by Carter Bradley, United Press Staff Correspondent (Bradley 4).

Legend has it that instead of entertaining him with rattles and toys, Mickey was given rubber balls and a bat to play with. At nighttime, when most kids listen to lullabies to help drift off to sleep, Mickey’s dad would turn on the radio so that his son could follow along to a ballgame before he shut his eyes. The moment the young boy possessed enough might to lift a bat was the moment he began cultivating his skills—knacks that went on to develop at a paranormal pace. To give the kid a full baseball experience, his father, Mutt, would pitch to him right-handed, and his grandfather, a southpaw, would throw to him from the left. In doing so, they would have the prodigy hit from both sides of the plate to help nurture his ability to swing as a switch-hitter. On the defensive side, his dad encouraged Mick, a natural righty, to practice throwing with both hands, as he was eager to see his son perfect the craft from every angle.

Though, by nine, after Mickey expressed serious frustration over how difficult it was to be an ambidextrous player, his father made a deal with the boy and allowed him to throw with just his natural hand. However, to honor the agreement, he had to continue hitting from both sides of the plate. If a lefty was on the bump, Mickey was to bat right-handed, and vice versa. As a major leaguer, Mickey wound up breaking this promise just one time, in a game against Washington where he batted from the right side of the batter’s box against a righty. “I just wanted to see how it felt,” he said after the event. “It’s no good for me. Dad was right. But then he was always right. Any success I’ve had, I owe to him” (qtd. in Bradley 5).

By the age of ten, weighing between 80-90 pounds, Mickey had already become a premier switch-hitter for the Douthat (Oklahoma) team in the Pee Wee League. According to his mother, Lovell, Mickey, much like the rest of the youth in America, developed his chops in the absence of vegetables. “My kids wouldn’t eat greens, or spinach, or okra or anything,” Lovell said in the aforementioned article written by Carter Bradley. “They always wanted a lot of milk, bread and meat. And they sure liked candy. Even now every time Mickey comes in the house he goes straight to the refrigerator and pours himself a glass of milk” (Bradley 4). When he was 15, Mantle hovered around five feet and weighed just 118 pounds. Then, over the course of the ensuing year, he rose up to 5-10 and 170 pounds. During this stretch, Mickey would swing a sledgehammer and perform other unique muscle-building actions while working with his dad, a lead and zinc miner, around the mine.

During his time at Commerce High, he shined on the ballfield, blacktop, and gridiron. His deep-rooted adoration for athletics trickled into the classroom. In the Carter Bradley article, one of Mantle’s former high school teachers, Miss Bertha Jacoby, recalled what it was like to have Mickey as a student. “When I had him in junior English he sometimes turned in the best themes in the class,” she said. “But baseball had the upper hand. His themes were invariably about athletics” (Bradley 5). While there was no question that Mickey was put on this Earth to swing a bat, those who witnessed his play at halfback on the football team believe that he may very well have received a football scholarship, had he not been incidentally kicked in the ankle during a scrimmage—an injury that occurred during his sophomore year that forced him to undergo a pair of medical operations. Unfortunately, the injury bug would follow him along throughout his professional career, but, like many greats, Mantle managed to prevail.

At 16, Mickey, who by this time was hitting moonshot homers from both sides of the plate and running at the speed of light, received attention from New York Yankees scout Tom Greenwade, who covered the states of Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. “What impressed me the most the first time I saw him,” said Greenwade in an interview with the Tulsa World while discussing his introduction to Mantle while he was still a teenager, “was his running. Boy, could he run” (Smith 12). A day after graduating from high school, Greenwade offered Mantle a baseball contract. Since he was only 17 at the time, Mickey’s dad had to sign for him. Just like that, Mickey was off to play for the Independence club Class D Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri League. In the deal, Mickey was set to receive $400 to complete the 1949 season with the team and was also granted a $1,100 bonus. In 89 games, he hit .313, which was just four points lower than the batting champion.

Due to his strong play, Mantle was promoted to the Class C Western Association for the following season. That year, as an 18-year-old in 1950, he was pretty much unstoppable. In 133 games for the Joplin Miners, Mantle posted a league-best .383 batting average, with 40 doubles, 12 triples, 26 home runs, and 136 RBI—not to gloss over the 22 steals he had also compiled. By showcasing that he could do it all, Mantle got the invite to Spring Training with the Yankees in 1951. As a 19-year-old kid, Mantle headed down to Phoenix, Arizona, a little bit before the actual players from the Major League team were scheduled to arrive for camp. During this period, with all the attention on the up-and-comers in the system, Mantle, displaying his ability to hit the mile and run like a track star, wowed everyone in attendance, including Yankees skipper Casey Stengel.

Exhibiting the potential to morph into a true, five-tool player at the big-league level, reporters began writing stories around the teen, which, for the time, was a rarity. Prospects would rarely ever get attention from the media, but Mickey was not just any budding ballplayer. He was a blue-chip player with limitless potential. Once the games began, the appeal for Mantle’s prowess continued to grow at an exponential level. In his second contest, Mantle, batting from the left, smashed a towering home run over the scoreboard at Phoenix Municipal Stadium for his second homer of the Spring. His first one came in the game prior, from the right-handed side. Later in the exhibition, he roped a ball off the right field wall for a triple. Mantle finished the Spring hitting .403, which encouraged Stengel to keep the teenager around with the major-league team to start the 1951 season. “This kid is absolutely tremendous,” the manager of the Bronx Bombers said at the time of his decision to have Mickey forgo the rest of his minor-league training to suit up with the big boys (qtd. in Jones 8).

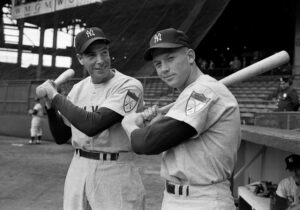

With DiMaggio holding it down in center, Mantle began the 1951 season in right field. After starting off in a slump, as his average sat at .222 (10-for-45) heading into May, the 19-year-old Mantle picked it up a bit as the season went on, but when his average dipped back down, Stengel decided to ship him off to the AAA team to refine some of his skills. Turns out, the brief demotion was exactly what the kid needed. In 40 games with the Kansas City Blues, Mantle got his swagger back, hitting .361 with 11 home runs and 50 RBI. His outstanding play in the minors earned him another shot with the major-league club, as he was called back up in late August. He wound up hitting .284 with six home runs during his second stint with the Yankees to close out the year, which earned him a spot on their World Series roster.

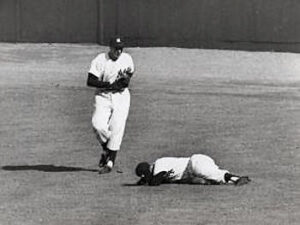

Still just 19 years of age, Mantle suited up in the Fall Classic against another rising star, the NL Rookie of the Year, 20-year-old Willie Mays, and the New York Giants. In the second game of the 1951 World Series, Mantle, who had opened the contest up with a beautiful bunt to reach base, which led to him scoring the Yanks’ first run, suffered a nasty injury on a flyball off the bat of none other than Mays. In the fifth inning, Willie hit a ball into right-center. DiMaggio, playing his last season, patrolled center, while Mantle resided in right. With the ball lofted between the two, both players headed over to track it. It is said that Casey Stengel told Mantle, prior to the contest, that Old Joltin’ Joe was running on a bad heel, so if there was ever a play to be made on a ball that was in DiMaggio’s vicinity, Mantle ought to go for it.

Taking that advice, Mantle darted after the ball. Moving as fast as he could, Mantle raced for the catch. The moment he was getting ready to throw his glove up and make a stab at it, DiMaggio, according to Mick’s account, said, “I got it,” and called him off (qtd. in Miller 15). The call from the Yankee immortal forced Mantle to slam on his brakes, a move that could not have been made at a worse time. Implanted in the outfield grass at the Polo Grounds where Mantle halted was a six-inch round depression. He stepped into the pipe, and his legs went out from underneath him. The teen was carried off on a stretcher and ruled out for the remainder of the series. He spent the night around his father, Mutt. The next day, unable to put any weight on his knee, the two headed off to the hospital so that Mickey could get some X-rays.

Once they arrived, to help with getting out of the cab, Mickey held his arm around his father’s shoulder. The second he put all his weight on his father, Mutt collapsed and, due to his lingering back pain that had been bothering him for months, could not get up. In a wild turn of events, the two wound up sharing a room in the hospital together and watched the rest of the World Series in each other’s company. Though the Yanks would go on to finish the job and win the championship, it was a tragic time for the Mantles. While admitted, Mutt was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. He was given just a few months to live and died the following May at 40 years of age.

After being told that no surgery was needed on his damaged knee, despite the severe wounds, Mickey ended up playing two seasons on a bum knee before getting an operation in 1953. Though he would never move the same following this freak injury, Mickey Mantle went on to have one of the greatest careers that a ballplayer could ask for. In 1952, prior to getting surgery to heal his gruesome injury, Mantle finished third in AL MVP voting while leading the league in OPS. The next year, he hit a tape-measure, 565-foot home run at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., which, to this day, is considered the second-farthest ball ever hit in a big-league game, runner-up to Babe Ruth, who, in the 1920s, is said to have swatted a ball that went almost 600 feet. Though the Ruth homer comes with its fair share of speculation, as it is believed that it was retrieved by a kid who picked up the ball and proceeded off on his bicycle, which made it impossible to measure where it had landed.

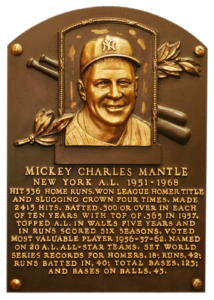

Mantle put it all together in 1956, when the Yankee great won the Major League Triple Crown, as he led all ballplayers, NL included, in batting average (.353), home runs (52), and RBI (130). To this day, while there have been other players who have captured their league’s Triple Crown title, no player since The Mick has finished a year beating out every other big leaguer in the three categories. He followed up this unprecedented season in 1957 by winning the AL MVP again, this time with an even higher average (.365). When all was said and done, Mantle would win three AL MVP awards, hit 536 home runs, and play in 20 All-Star Games. Lord knows the kind of numbers he would have put up, had he avoided the injury bug.

Including the 1951 series where he got hurt, Mantle appeared in 12 World Series for the Yankees and was victorious in seven of them. To this date, no player in the history of the sport has walked more (43), scored more runs (42), hit more home runs (18), has had more RBI (40), or racked up more total bases (123) in career World Series games than Mantle. Though he retired earlier than most, Mantle played 2,401 games with the Bronx Bombers, which is second all-time in the franchise’s storied history. In 1974, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first try.

With the level of attention that baseball received, in comparison to other major sports in the 50s, competing at a time where a TV set was becoming a living-room staple across all households, all blended with his unique, fable-like backstory and unparalleled play on the ballfield, Mickey Mantle morphed into one of the most notable and lovable athletes in the history of American sports. Despite the personal tragedy and physical impairments, Mantle overcame it all and will be forever remembered as a larger-than-life hero. In a 1989 interview with The Dallas Morning News, NBC announcer Bob Costas, who, at the time, carried a Mantle baseball card in his wallet, summed up the captivation of Mantle’s career perfectly. “Anyone who saw him play realizes the numbers in the Baseball Encyclopedia don’t do him justice,” Costas said. “It was what he symbolized. Playing with the Yankees, he was placed in a dramatic setting. He was flawed to injury and never able to attain that greatness. He was dealt with a bad hand but was still great. There are elements of Greek tragedy to it” (Taylor 7).

Even in his later years, when he spoke openly about his bouts with alcohol, personal regrets, and other mishaps, the public appreciated him even more. Here was a monumental icon who, when push came to shove, was humble enough to admit his faults to the world—a sign of humility that further captivated his astronomical audience of supporters. His death in 1995 penetrated the hearts of these enthusiasts and all those who knew him. “Mickey meant an awful lot to me,” said Henry Aaron at the time of Mickey’s passing (Brown 3). Bob Gibson, who faced Mickey in the 1964 World Series, said, “They’re going to remember him for being the catalyst for the Yankees all those years. He was a pretty damn good ballplayer” (Brown 4).

“He was a tremendous athlete,” said Don Mattingly, the captain of the Yankees (Brown 5). “Mickey was a great, great player in the organization and a mythical figure in baseball.” While holding back tears in remembrance of Mantle, Yankees announcer Mel Allen was quoted saying, “Mickey was a country boy who came to the big city and became one of the greatest and most powerful switch-hitters who ever lived. He was the most exciting player since (Babe) Ruth and (Joe) DiMaggio, a big leaguer in every way” (Brown 6).

In a weird way, Mantle’s death served as a reminder to the followers of the sport that this simple, yet ever-so-complex game is a beautiful one, even on days or years where it may appear otherwise. Like Mickey, the game of baseball comes with its share of flaws, but in the end, there is nothing quite like it.

Works Cited

Bradley, Carter. “Mickey Mantle: Country Boy to Yankee Star.” United Press, 15 June 1956, pp. 4-5.

Brown, James. “Baseball Mourns Mickey Mantle.” Associated Press, 14 Aug. 1995, pp. 3-6.

Jones, Robert. “Stengel Bets on Mantle.” New York Times, 20 Mar. 1951, p. 8.

Miller, Thomas. “Mantle Recalls 1951 Injury.” Sports Illustrated, 10 Oct. 1960, p. 15.

Smith, John. “Scout Greenwade Discovers Mantle.” Tulsa World, 12 June 1949, p. 12.

Taylor, David. “Bob Costas on Mantle’s Legacy.” The Dallas Morning News, 5 May 1989, p. 7.