In 1990, three years before the Florida Marlins and Colorado Rockies joined the league, Opening Day was pushed back a week due to yet another gripe between the owners and players. For those in the know, this shutdown was the seventh since 1972, after decades of consistent play without a significant lapse. All of a sudden, it was just as common for the audience to have to sit through a strike, whether minor or major, as it was for them to experience a Triple Crown winner in the American League. Since runs batted in became an official statistic in 1920, there had been seven seasons in which a player led the league in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in, in the same year: Jimmie Foxx (1933), Lou Gehrig (1934), Ted Williams (1942), Ted Williams (1947), Mickey Mantle (1956), Frank Robinson (1966), and Carl Yastrzemski (1967). Seven Triple Crown winners in the AL, and seven strikes.

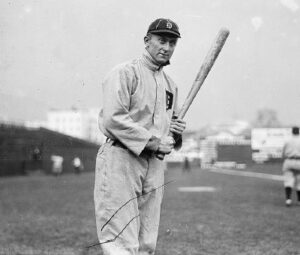

One of the few men who achieved the above parameters, prior to 1920 when RBI was unofficially cataloged, was Ty Cobb (1909). At the tail-end of his illustrious career, Cobb predicted the ensuing predicaments that baseball would end up running into, due to the almighty dollar. In his eyes, by the mid-20s, the financial aspect of the game had already tainted the sport that he had dedicated his life to. In the words of Byron Bancroft Johnson, founder of the American League, when speaking on the legacy of the star outfielder, he said, “He did more for baseball than any single individual that ever lived” (qtd. in Salsinger 87). So when Cobb talked about America’s Pastime, his words carried tremendous weight. In the first authorized biography written about Cobb, American sportswriter H. G. Salsinger included a chapter titled “In His Wake,” which was a section dedicated to Cobb’s outlook on the modern-day game as he was preparing his exit from it. Published in 1924, the referenced branch in the book starts out with Cobb’s disdain for the “lively ball.” Prior to 1920, Cobb shined in what is known as the “Dead-ball era,” a period in baseball where a number of rules in place were streamlined to effectuate a boost in offensive output. For example, in the Dead-ball era, it was commonplace to use the same ball throughout all nine innings of action. Should the ball show any significant signs of fray, only then would it be replaced. On top of keeping the same pill, the pitchers were allowed to impair it to their liking, oftentimes scuffing it, rubbing dirt on it, cutting it with an emery board, and, most infamously, spitting on it. If the ball went out of play, by way of a home run or a foul ball, those in attendance would return it to the field, and play would resume with it. Quite obviously, by wearing out the same ball, whether it be because of a deliberate action by the pitcher or just the nature of the sport, the abatement to the ball’s natural limberness made it much harder for hitters to square it up with force as the games prolonged. As a result, there was not much scoring, particularly when in comparison to the time in the sport where a foul ball was not ruled a strike. Before 1901 in the NL, and prior to 1903 in the AL, a foul ball was not deemed a strike, so when this change came into effect, mixed with how the ball was being treated, the numbers took a hit.

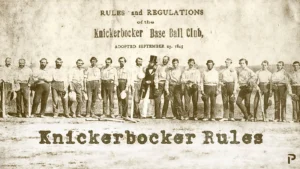

Staying on the topic of the primary object used within the sport, along with updating the rules, the decline in scoring amid this aforementioned period was also due to the physical makeup of the spherical pill. When the sport was pioneered by the Knickerbocker Baseball Club of New York in the mid-1840s, the ball used was homemade. It was raw and manufactured with strips of old rubber shoes as its foundation. The bedrock of it was wound with dated stocking yarn and shielded with cowhide. In 1865, the year when soldiers returned from the Civil War, baseball was nationalized. As a result, a small factory in New England became the primary manufacturer for the game’s ball.

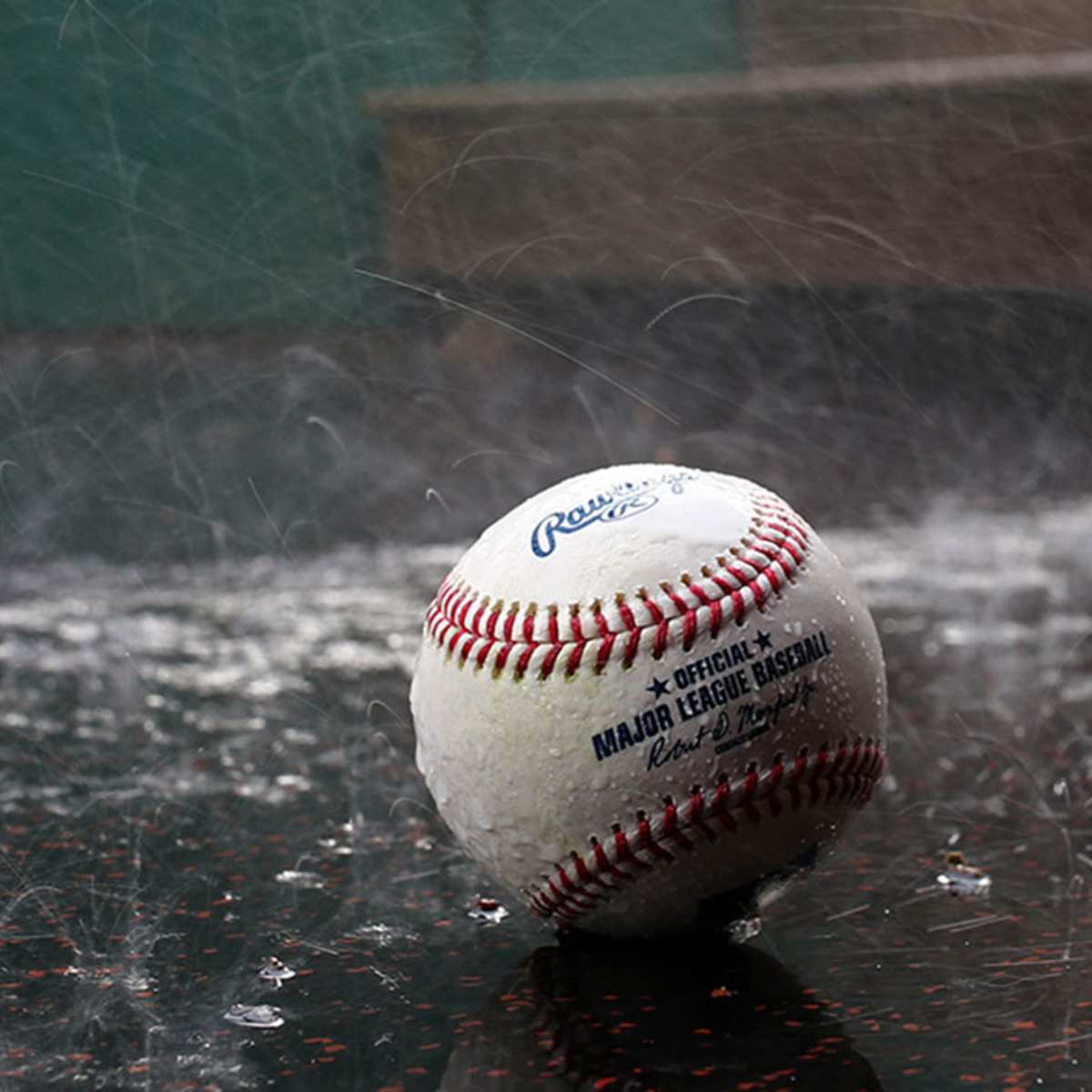

As the years prolonged, and the game got bigger and bigger, additional operatives wanted to capitalize on the popularity of the sport, so they too began constructing baseballs. Soon enough, every well-known team had their own regional designers, whose sole responsibility was to construct a baseball that best suited its local club. Since the home team was responsible for supplying the ball for all games that took place on their own field, to give themselves the best chance, they would have the ball tailored in accordance to their inherent knacks. For example, if a team struggled at the plate and was known more for their defensive skills than their hitting abilities, they would have a soft dead ball supplied for them, one that, believe it or not, could very likely have been smashed with a mallet before the contest to ensure that neither side would be able to do much on the offensive end. On the flip side, if a team relied on their offensive output to carry them to victory, then they would use a very hard lively ball. Therefore, baseball jockeying, prior to the first pitch even being thrown, was rampant, and the visiting ball clubs would not have a clue as to what kind of ball was in play until the action began. The inconsistency with the nature of the pill, as it varied from city to city, led to a wide range of outcomes across the sport. One team could very well put up double-digit runs in their home city, then, the next game, get shut out in an event on the road. Soon, the players and followers of the game caught on to what was happening, which led to alterations. To protect the integrity of the sport, the National League, in its inaugural year, 1876, decided to have an official ball made for championship games. However, due to the league’s lack of specification, the “official” manufacturer continued to make balls that were custom-made for each team. To combat this mishap, the NL outlined more stringent regulations. A major stipulation being that every ball must be manufactured akin to one another and assembled in individual boxes with a seal to ensure that the object would not be meddled with. Over and above, in order for a ball to be considered “game-worthy,” an official of the league was asked to inspect the ball and put his signature on it, in an effort to certify its authenticity. This is why if you have ever purchased an official Major League ball, it is marked with the commissioner’s autograph. With the new provisions, there was far less discourse surrounding the essence of the ball, but, due to the aforementioned ways that players would tamper with it, the league continued to examine and refine it. In 1910, the officials changed the center of the ball from rubber to cork. In reference to the reasoning behind the alteration, Popular Mechanics, at the time of the shift, noted, “The cork makes possible a more rigid structure and more uniform resiliency. It is said to outlast the rubber center balls many times over, because it will not soften or break in sports under the most severe usage” (“New Baseball” 45). The modification to the pill led to an uptick in hitting, as its new substance allowed hitters to drive it with more force. Yet, the pitchers at the time were quick to make adjustments and did what they needed to do to control the game. Soon enough, the numbers dipped back down.

In any regulated operation, when numbers are not good, changes must be made. Beginning in 1920, if a ball showed even the slightest sign of erosion, it was immediately replaced with a fresh one. On top of ensuring that a pristine ball would be used around the clock, those throwing these brand-new balls were prohibited from adulterating it in any manner. No more foreign substances, no more scuffing, and no more spitting. Unless you were one of the seventeen “spitballers” who were grandfathered in, as these lucky few were allowed to keep expectorating on the ball until they retired.

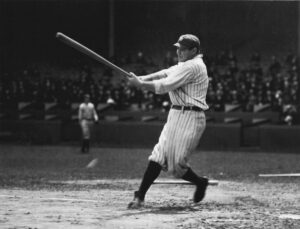

With the new rules set in stone, the game changed overnight. In 1920, New York Yankees star Babe Ruth clubbed 54 home runs, shattering his previous high of 29, the former record that he set in the year prior during his final season with the Boston Red Sox. Though Ruth was somewhat of an outlier when it came to his power, as he ended the year hitting more home runs than 14 of the other 15 teams competing in the AL and NL, offensive numbers went up across the league. Along with the updated guidelines, many players at the time believed that the league tampered with the ball, speculating that the league added more rubber in it than ever before. Some went as far to say that the AL was using a livelier ball than the NL was, which is why Ruth was able to smack so many more out of the ballpark. The ball makers themselves, when interrogated on the matter, disputed the claim that there was more rubber or cork in the balls used in the 1920 season when in comparison to previous years. However, representatives from Spalding, who manufactured the official ball of the Major Leagues through the 1976 season, did not question the ball’s enhanced speed off the bat, claiming that the modern, Australian yarn used in the balls at the time had a stronger tension, which meant that they were wound tighter, giving them a boost in elasticity. When Ban Johnson was asked about the subject at hand, the AL president defended Spalding’s claim, attributing the ball’s noticeable acceleration off the bats to the use of quality yarn. Because of the implications that stemmed from World War I (1914-18), the best yarn at the time was unattainable, so the league, for years, was forced to use a cheaper grade, which meant the ball was wrapped more lightly, weakening its speed off the wooden stick.

As the years transpired, the league made constant adjustments to the pill. Some changes were public, and others, in the eyes of conspiracy theorists, were done in secret. To this day, debates surrounding the essence of the baseball continue to pop up any time a season entails some sort of spike or abnormality in hitting. Whether the league took deliberate action in 1920 to alter the heart of the ball or not, the constant “unknown” of its crux makes the game that much more interesting. After the uptrend in hitting carried over into the 1921 season, making it apparent that the game was setting foot in a new era, prominent individuals in the sport spoke about the proliferation on the offensive end. Most notably, iconic player and manager John McGraw, who, at the time of his comments in 1921, served as the coach of the New York Giants. A baseball purist through and through, who began his professional career in the late 1800s, McGraw, right off the bat, believed that the lively ball would do more harm than good. “At first the slugging was a novelty,” said McGraw in a 1921 interview published in The Kansas City Kansan, “because the home runs, once infrequent, stirred up the fans. But now that everybody is knocking out four-baggers, the public is getting weary. Players who, in former years, couldn’t hit the ball for more than two bases, are driving it over the outfielder’s heads into the bleachers” (McGraw). In that same discussion, when asked about the ball itself, McGraw referred to the new pill as “lively and also too glossy” and later offered up advice to the powers that be: “If the magnates want to save the game, they’d better go back to the ball in use two or three years ago and also modify the restrictions put on the pitchers” (McGraw).

When Salsinger asked Cobb about his opinions on the “lively ball” for his story, a few years into the fresh epoch, the hot-tempered, ever-so-iconic Detroit Tigers centerfielder, like McGraw, did not mince his words. “The lively ball has robbed the game of its finesse,” said Cobb. “The art has been taken out of baseball. A premium has been placed upon brawn instead of brain” (qtd. in Salsinger 92). Cobb would go on to reference the assumed agenda being pushed, which was to create games with more powerful base knocks, resulting in a rise in runs, as that is what the people pay to see, though he was quick to push back on this perceived sentiment: “Too much hitting causes overbalance. The public will tire of too much of anything in any sport. You can even have too much of such a good thing as extra-base hits” (qtd. in Salsinger 92). In his eyes, the lively ball removed the strategy aspect of the game, citing that there were fewer bunt attempts and fewer players trying to swipe bags. Referencing an actual scenario, Cobb talked about how trying to steal third from second would now be considered a “bone-head play” for a number of reasons, one being there was now a greater chance that your teammate would drive the ball far enough for you to score with ease from second. This uptick in probability that a player would connect with a healthy amount of power meant that the outfielders were now forced to play 20-30 feet further than in years prior, making it even easier for a runner on second to come home. “The thing to do with the lively ball in play was to stay anchored to a base and wait for the hit that was almost sure to come. . . . Teams no longer played for a run, but they played for runs” (qtd. in Salsinger 93).

As the chapter went on, Cobb talked about the game always moving in “cycles” and that this period was just another one of them. “When I first broke into the league, the craze was pitching,” he said. “All kinds of freak deliveries began to appear: the shine ball, the emery ball, the spitball, and all of the freaks. Then, suddenly, there was complete reform. All freak deliveries were made illegal. Pitchers could not apply dirt or anything else to the ball. Baseball went from one extreme to the other” (qtd. in Salsinger 94). When alluding to the present game at the time of this discussion, Cobb stated, “This is the day of the slugger. And tomorrow—who knows?” (qtd. in Salsinger 94). A player with a superhuman ability to hit for average, but also a man with prophetic visions on the sport he dedicated his life to.

In the very next section of Salsinger’s book, a section titled “The Dollar,” Cobb continued to predict the future of the sport. “There is not the same love for baseball among the average players today that existed among the average twenty years ago,” he said. “One reason is the dollar. Salaries have gone up tremendously.” For reference, when Cobb was at his peak in the first fifth of the century, he was making $9,000 a year. At the time of his interview in 1924, Cobb, operating as a player/manager in his late 30s, earned an annual salary of $50,000. “When I broke in, ball players had a love for baseball. The salaries were small, compared to the salaries of today. The pay was not the big attraction, but the game was” (qtd. in Salsinger 95). In the ensuing paragraph, Cobb stated, “When I broke in, we had ballplayers; today, we have businessmen” (qtd. in Salsinger 95). Though he was not around to see the game’s first and eventual “stretch” of strikes, it is safe to assume that the man who collected 4,189 hits, while posting an MLB record .366 lifetime batting average, saw the mighty dollar creating tectonic friction from a mile away.

Works Cited

McGraw, John. “Interview with John McGraw.” The Kansas City Kansan, 1921.

“New Baseball Has Cork Center.” Popular Mechanics, vol. 14, no. 1, July 1910, p. 45.

Salsinger, H. G. Ty Cobb: His Life and Times. Sports Publishing, 1924.