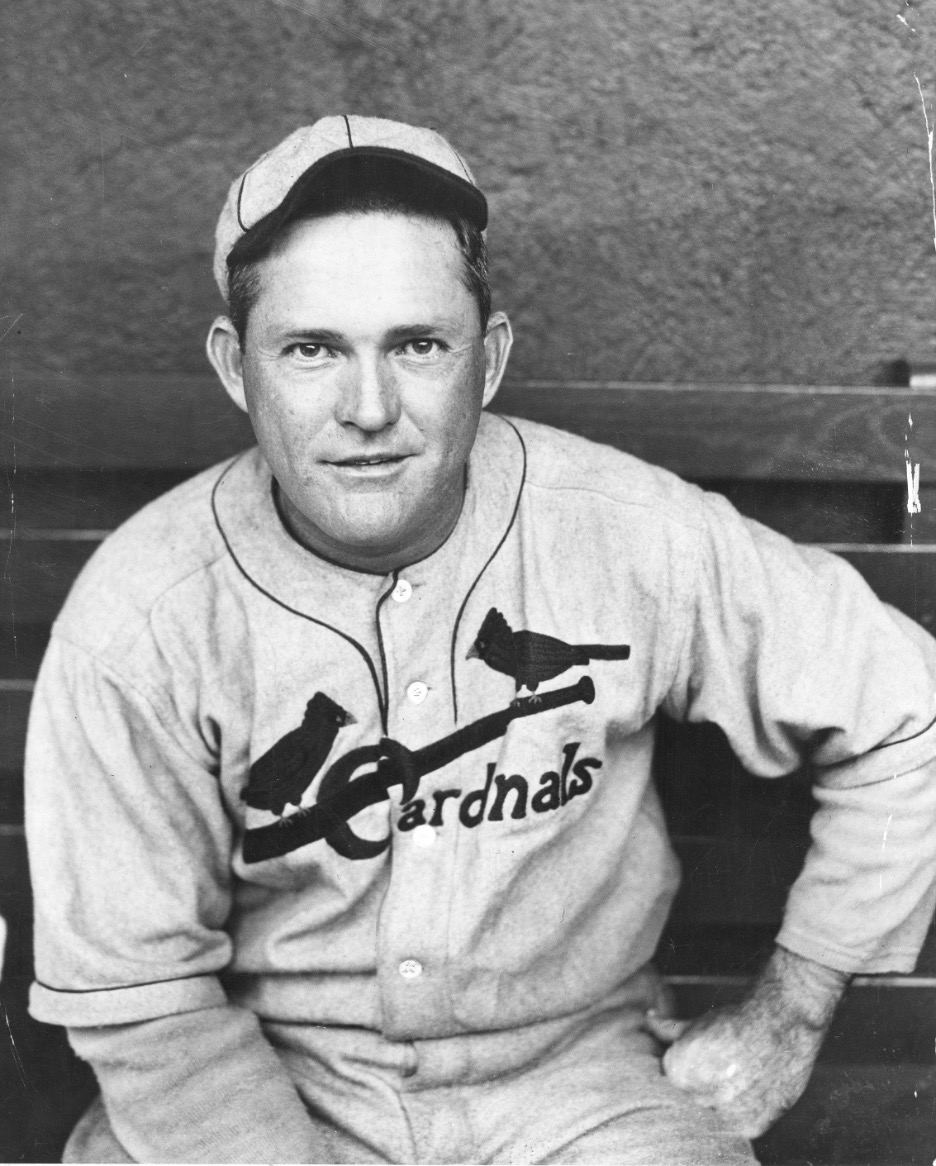

“Hornsby is the first player on the field, the last one off,” said St. Louis Cardinals manager, Branch Rickey, when speaking on his star second basemen in an interview with sports editor, Billy Evans, at the top of the 1923 MLB season. Mind you, the man receiving praise for his impeccable work ethic, had just wrapped up a season where he won the National League Triple Crown, and set the league’s new single-season home run record . Along with leading the NL in batting average (.410), home runs (42), and RBI (152), Hornsby, for the third-straight year, ranked first in all of the following categories: hits, doubles, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and total bases. Simply put, he was the face of the NL, and had Babe Ruth not existed, would have been the poster child for the best ballplayer of the 1920s.

“He simply never gets enough of baseball,” continued Rickey in the discussion. “Open dates are an eyesore to him. Most players welcome them. Hornsby is always wishing an exhibition game could be arranged. Regardless of the score, he never wants to get out of a game. Often I want to rest him up by taking him out of a game that seems a sure victory, or a certain defeat, but he always kicks against it.”

To cognize Hornsby’s indelible love for the game, let’s take it back to the beginning. A dimple-faced kid from Texas, Hornsby started practicing baseball at a very young age on the lots of Fort Worth. In his own words, when reflecting on his origin story, Hornsby once said, “baseball became the big thing in my life before I was ten, and I suppose it will be my life always.” The moment he got the itch for the game was when his mother made him his first uniform out of blue flannel. “It was one of the happiest moments of my life when I first got into it (the uniform),” said Hornsby in a self-published piece advertised in The Atlanta Constitution in 1929. “I knew then that I wanted to be a star ballplayer when I grew up.” When he first started getting familiar with the game, he received some harsh criticism from his older brother, who was a semi-pro ballplayer himself in the area. After a game in which Rogers thought he played alright, his brother told him, “Kid, you’ve got a lot to learn, but keep on hustling.” According to Rogers himself, the commentary from his kin didn’t stop him from pursuing his passion. “I continued to try, because I loved to play ball, and I felt an urge to make good, even if I my brother didn’t think I could.”

Guided by his enthusiasm, Hornsby positioned himself to get a real shot at making it big. He began playing in the minors in 1914, at the age of 18, thanks to the help of his brother, who convinced the manager of a local ballclub to take a chance on him. “I had visions of the big leagues right then and there,” said Hornsby when touching on this time. “Maybe in another year or two, I would be in the big show with Cobb, and Eddie Collins and Christy Mathewson.” After his older brother got him the job, he told Rogers that if he played well, then maybe, just maybe, he could become a regular player in “some class B League.” Despite the underwhelming thoughts on his future, Hornsby noted that, even after hearing his brother’s low expectations for him, “I refused to quit dreaming.”

In his first year at the amateur level, suited up for a team out of Denison, TX, Hornsby didn’t flash much of any talent, as he hit just .232 in 114 games. In his next season, though he made some slight improvements at the dish, Hornsby’s average still resided well-below the .300 mark. From a physical standpoint, he was a frail figure, who weighed in at around 140 pounds. Even though his numbers didn’t pop off the charts, and he didn’t possess what one would deem a ‘promising build’ for a professional athlete, Hornsby’s aggressive approach caught the eyes of a spectator, who, by trade, was a railroader, but by heart, was a fortune teller. A man with mystic like powers who foresaw Hornsby’s future as a standout in the Major Leagues.

The story goes as followed. During the 1914 season, the St. Louis Cardinals spent the bulk of the year clashing with a pair of titans, the Boston Braves, and the New York Giants, for the National League pennant. If the Red Birds were going to have any shot at winning it, they knew they had to be on their p’s and q’s, which in baseball, meant that every position player had to carry their weight, and then some, for the ballclub to reach their collective goal. As the season transpired, a glaring weakness formed in between second and third. The team’s everyday shortstop, Art Butler, who played on the same team as Honus Wagner in the two years prior to joining the Cardinals, was unable to absorb even a fraction of Wagner’s abilities when it came to his play. At the plate, Butler hit .201. On the defensive end, he was even worse. In his 86 games at shortstop, he recorded 30 errors. In an attempt to salvage the season, the team decided to convert their first basemen, Dots Miller, into a shortstop, but, like Butler, Miller wound up making blunder after blunder. The then manager for the Cardinals, Miller J. Huggins, with the season on the line, had seen enough, and, according to The Plain Dealer, who covered this matter, said aloud for all to hear, “Get me a shortstop and I’ll win this pennant.” As luck would have it, one man followed up to Huggins request, and made sure that the skipper would get his memo. After getting shut out in contest against the Braves, which lowered the Cardinals from 2nd to 3rd place in the pennant race, Huggins, bottled up with infuriation and disgust from his team’s rotten performance, arose out of the team’s dressing room with no desire to converse with others about the poor play. Much to his surprise, he was greeted by a random fan. Before he could overlook him, the stranger spoke up.

“You’re Mr. Huggins, aren’t you?” said the baseball enthusiast. “Well, I’m Charley Reese – you don’t know me, and I don’t know you. I’m a conductor, a railroad conductor – travel between St. Louis and Texas. They all tell me you’re trying to get a shortstop. I’ll give you a tip on one – a kid down at Denison, Texas. Look him over!”

With little to no interest in engaging with the man, as it wasn’t the first time, and certainly not the last, where a supporter had offered up a player recommendation to improve his team, Huggins brushed off the lead. Though hard to scale for certain, it’s possible that once the man revealed his occupation, the skipper’s mind populated a mental scene of a day in the life of the honest worker that stood before him. Collecting train tickets, ensuring that all on deck are safe throughout the ride, verifying that the tracks are scot-free from any and all impediments, and working close with the rest of his crew to guarantee a successful trip. How could a man who does all that for a living, all while sporting a railroad engineer’s cap, possess the insight to foresee who should be donning a Cardinals hat?

Instead of listening to the train manager, Huggins, with a fractured team or not, opted to push on with the pieces they had. In doing so, the Cardinals finished the year in 3rd, 13 games behind the pennant winning Boston Braves, who wound up sweeping the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1914 World Series.

The following spring, while the entire organization, including both the major and minor league ballplayers, trained for the upcoming year down in San Antonio, TX, Huggins, in his days away from the field, would host regular sit-downs with one of his talent scouts, a man by the name of Bob Connery. With the hopes of manufacturing better results on the field, Huggins, in one of their meetings, asked the recruiter, “Say, Connery, are we near Denison, Texas? Remember that fellow last summer who said something about a shortstop at Denison, Texas?”

Once the manager referenced the potential prospect, the two mapped out an immediate plan. Huggins, who had received another tip on a local Texas player, a middle infielder named Mike Massey, was set to bring the Cardinals first-team to Austin, TX for an exhibition against Massey and the University of Texas ball team. While Huggins scouted Massey, Connery was informed to bring the second-team to Denison so he could get a good look at the kid that the conductor recommended. In the coming days, the two went their separate ways. By the time Huggins caught up with Massey, it was already too late. The collegiate star had given his word to Joe Birmingham, manager of the Cleveland ballclub, that he would sign with the Indians. A week later, when Huggins reconvened with Connery, he asked the scout how his prospect looked, to which Huggins replied, “A little light, Hug (Huggins), and I don’t like the way he stands at the plate.” With Massey out of the equation, and Hornsby not drawing enough interest, the Cardinals rolled the dice, and trotted into the 1915 season with another glaring question mark between second and third. As expected, production, or lack thereof, by their shortstop, was , once again, a discernible issue. In the middle of the season, Connery, with hopes of rescuing the ballclub’s chance at glory, went back to Huggins and said to the skipper, “Hug, remember that lad down in Texas I looked at during the Spring? Well, I’m going to take a chance on him. If I can get him cheap, we might be able to do something with him. What I fancy about him more than anything is his pep – yes, they call him ‘Pep’ because he’s talking and fussing around continually. There are too many silent players on our club – that’s why we’re seventh.”

With the team out of logical moves, and falling fast in the race, Huggins agreed to take a chance on the kid who, at the time, exuded more passion for the game , than aptitude. In September of 1915, Rogers Hornsby, who was purchased from his amateur club for $750, became an official member of the St. Louis Cardinals. According to The Plain Dealer, 10 minutes into his first practice with the team, Hornsby’s uniform was coated in dirt. Throughout the workout, he dove after ground balls, called out teammates who made errant throws, and even questioned Huggins’ ability to hit adequate infield grounders. After day 1 was in the books, Connery asked Huggins what he thought of his new infielder, which the manager replied, “Hasn’t any style about him, but you’re right – he’s fresh, full of energy, and in four of five years he might be ripe.”

Joining the team at the tail-end of the regular season, Hornsby played in 18 games, and, in alignment with Huggins’ thoughts, wasn’t ready to blossom just yet. In 57 at-bats, he hit just .246, with zero home runs. Of his 14 total hits, only two of them went for extra-bases. In the rare occasion that he did reach safely, Hornsby did so on weak pop ups, or lucky rollers through the infield. Though the sample size was minimal, at years-end, Hornsby, curious to get his new manager’s thoughts on his play, asked the coach for a proper evaluation, to which Huggins replied with, “I’ll tell you son…You’re a little light for this big league stuff – might be able to do something for you next spring, but I guess I’ll have to farm you out.” Rather than combatting with his coach over his decision, Hornsby took it on the chin, and not another word was said between the two. Fast-forward to the winter, where Hornsby received an invitation letter for Spring Training at the team’s practice grounds in San Antonio. That Spring, Hornsby caught Huggins, and the rest of the team, by surprise. No longer was the so-so performer dwelling in a frail figure. As is said in the Plain Dealer report, “he hopped from a lightweight to a near heavyweight. The shirt pinched the neck, and from the hips up, he looked like a wrestler.”

Shocked at the transformation, Huggins went right up to Hornsby to get an understanding of what had transpired since the last time the two met face-to-face. While Huggins was dumfounded, Hornsby was anything but. “Didn’t you tell me to go out on a farm?” he posed to his manager. “Didn’t you tell me I was too light? Well, it’s been the farm life all winter for me with nothing but fresh eggs, milk, and the country air.” As strange it sounds, the kid from Texas misinterpreted Huggins recommendation to get some quality reps in a farm-league, and took his words a bit too literal. Yet, as a result, despite taking the least logical path, Hornsby, from a physical standpoint, had morphed into a real big-leaguer.

Along with his new stocky frame, Hornsby had also reinvented himself at the plate. When he stepped into the batter’s box, he did so with a longer, heavier bat, and positioned his feet in a brand-new location. Deep in the box, and farther away from the plate than before, Hornsby began to drive the ball all around the field. He granted those in the outfield a nice cardiovascular session as his long-flies forced the fielders to run to the fence to retrieve the tattooed balls. On the defensive end, his bulked-up figure allowed him to throw with accuracy on grounders blasted deep in the hole between short and third.

Though Hornsby had made immense strides in just a matter of months, due to the fact that his maturation as a ballplayer came out of the blue, the Cardinals, going into Spring, had already deemed Roy Corhan, a Pacific Coast League standout with major league experience, as their everyday shortstop for the upcoming season. However, during the final week of camp, Corhan reported soreness in his arm, and was unfit to compete for the time being. With spring games approaching on the calendar, the Cardinals, yet again, were in a state of uncertainty when it came to the one of the most vital positions on the field. Once it was clear that the position was up for grabs, and needed to be filled in the immediate future, Hornsby begged the staff to take a chance on him. “Don’t worry, don’t worry, Hug, send me in against those American League pitchers; give me a crack at them,” he pled to his coach. With nothing to lose, and nowhere else to turn to, Huggins and Connery agreed to give the kid a chance. Since Rog was Connery’s guy, the scout spent time as he could with his sought-after prospect to get him caught up to speed. Following the team’s standard drills, Connery would ask Rogers, and a few others, to hang around on the field for extra work. This is where Rogers would take additional ground balls, and soak up as much knowledge as he could from the scout. While most would find the work tedious, Hornsby couldn’t get enough of the additional practice. In 1929, Hornsby wrote about this period of his life in the Star Tribune, and was quoted saying, “I never got tired of it, and perhaps my willingness to work caused Bob to take so much interest.”

As luck would have it, Hornsby’s persistence, and devotion to the craft paid off in immediate fashion. In the 6th inning during the team’s first Spring game against the Browns, with the game knotted at zero, and a pair of runners on base, Hornsby trotted up to the plate. Moments later, he smacked a triple off of the right field fence, giving the Red Birds a 2-0 advantage. After the Browns tied it up in the seventh, Hornsby, batting in the exact same spot, with two men on, roped another triple to give his team a fresh two-run lead. The Cardinals wound up winning the exhibition 4-2, with all four runs coming from the remodeled Hornsby. From that point on, Rog was handed the keys.

Once the season began for good, Hornsby, now a mainstay in the Cardinals lineup, fell back down to Earth. Through the team’s first 30 games, the impassioned kid from the Lone Star State, while played in every contest, posted a batting average of just .260, and had hit just one home run. Despite the poor start, Hornsby refused to crumble, and kept his sights set on becoming a star in the field that he cherished. Abiding by the “first one in, last to leave” mentality when it came to his craft, Hornsby maximized every active moment he had to improve. After games, instead of exiting the ballpark with all of his teammates to get some rest or partake in an activity to his mind off of baseball, Hornsby would wait for all the fans to depart for the premise and proceed to gather up a crop of kids in the area and host a 30-minute batting practice session. The more he worked on his hitting, the better he became. By year’s end, Hornsby’s average sat at a cool, .313. The next season, he batted, .327 and led the league in triples with 17. After a few years dabbling between various positions, Hornsby found his home at 2nd base, and would go to become the greatest hitting second basemen of all-time. Amongst all players who qualify, Hornsby leads all 2nd basemen in total seasons (8) batting above .350, and it’s not even close. Trailing behind him is Rod Carew, who put together three such seasons. Over the entirety of his career, Hornsby, in 1,555 games serving as his team’s second basemen, hit .376, with an on-base percentage of .455 and a slugging percentage of .624. If you’re wondering how those numbers stack up against the rest of the men in baseball who have played at least 1,000 games at second, he ranks as follows: 1st, 1st, 1st. Not too shabby for a kid who struggled as an amateur, and, as strange at sounds, relied on the word of a railroad conductor to get himself a look at living out his dream of becoming a top-tier ballplayer. In the midst of historic run, located near the bottom of a write-up dedicated to Hornsby, The Salt Lake Tribune, summed up the man’s love for the game in a telegraphic, yet ever-so-eloquent manner. “You will never see Hornsby climb the Woolworth building to blow out the lights. Broadway, Main Street, and Hollywood hold no charms for him. He does not vote the prohibition ticket, but he neither smokes, chews, nor sips anything stronger than one-half of 1 percent. His greatest hobby is baseball.” From his own vantage point, Hornsby, late in his professional career, credited his ability to remain faithful to his dream as the impetus behind his success. When Hornsby was a boy, his day dreams were about baseball, and he looked at Ty Cobb as the real-life personification of a kid, like himself, who brought his vision into reality behind a deep-rooted love for the game. “The day dreams of youth, properly followed up on, have brought many a man out of obscurity and made him a world figure,” he said in 1929. “If boys ever stop having day dreams, then, when they grow up, they will not advance to such heights in business, science, art, and I might add, baseball.”

In a field where many of the greats from the past appear to have had possessed a natural knack for the game, even well before the public cheered them on, Hornsby is somewhat of an anomaly amongst his upper-echelon peers. Instead of banking on his inherent skillset as the foundation to improving along his baseball journey, he leaned on his love for the craft to propel him to unthinkable heights. As outlined, the opening chapter of his baseball career was anything but riveting, but with an unwavering appreciation for the game, as the pages turned, the story became more and more amusing. By the end of the book, he had published one of the most-compelling stories one can get their hands on when scanning the shelves of baseball’s best.

A strong degree of love, both love for self, and love for whatever it is you are concentrating on, is the cornerstone for putting forth potent energy in this realm. Regardless of his outcomes, or the words thrown his way at the beginning stages of his career, Hornsby safeguarded his dream with all his might thanks to his emphatic desire to become a star in the big leagues. This desire was shaped out his fixed love for the game, which Hornsby expressed through his commitment to improving. When working on materializing your own dreams, call upon your adoration for the specific visions to inspire you forward. Your heightened level of reverence for your ambitions is a plush source of power. A robust tank of fuel that will push you through when times get tough, and be there at the finish line with you when your goal is met. As often as possible, recall your love for the objective at-hand to help remind yourself why this particular aim must externalize itself in reality. After recapturing it in thought, exemplify your enthusiasm by showcasing it in the work needed to make your dream come true. The more love one has for what they are focusing on, the more of an advantage they give themselves amid the materialization of the effort. Possessing the ability to love someone, or something, at an unmitigated rate is a boon unlike any other, as its horsepower is matchless. Comprehending this, all dreamers must aim to always walk around in a love-infused figure. This target requires no level of skill, and has no barrier of entry. To sense love is an effortless choice made from within, that shall be made, time and time again, to generate great results. Resembling how Hornsby operated in relation to his regard for baseball, do not allow anything in this world to alter your sense of adulation for whatever it is in life that you prize. Shield your veneration with all your strength, as it is the key to unlocking the door to what your soul treasures the most. Independent of all outcomes, maintain your allegiance to your desires by feeding them outright deification.

When you express love, you sense the strongest degree of enjoyment, which allows you to become level with the present moment. The ‘now’ is when all great moments occur, as everyone’s most-cherished times play out in the absence of thought.

LIFE LESSON: Lean on your elevated level of love in your selected zone to skyrocket you to supremacy.