From 1920-1929, Babe Ruth hit 40 or more home runs in eight of the 10 seasons. In the two years that he missed the mark, Ruth was suspended for a portion of one of them and ill for the other, causing him to miss a significant number of games. By the end of the 20s, just five players not named Babe Ruth joined the 40-home-run club. Though more names added themselves to the elite group that Ruth founded, they came to the party either by themselves or with a handful of others. In 1922, the year Ruth was suspended, Rogers Hornsby hit 42 home runs and stood alone as the sole member of the 40-home-run group that year, thus making his light beam in baseball lore. In 1927, when Ruth hit 60, his teammate Lou Gehrig got in on the fun, clubbing 47 en route to being the only other ballplayer to hit 40 or more that season.

In the ensuing years, while a fresh set of names wound up making their way into the exclusive club, there was never a year, up until 1953, where more than three players hit at least 40 home runs in the same season. So for the few stars who did, like Mel Ott, Joe DiMaggio, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, Ralph Kiner, and Ted Williams, to name a few, due to the increased adoration for the long ball, exceeding the 40-mark meant an enhanced level of appreciation from the devout supporters of the game. Like Ruth, it gave mortal ballplayers, those few and far between, a sense of holiness. These supreme players stood out among the pack.

When Mickey Mantle hit 52 homers during his Triple Crown season in 1956, he and Duke Snider were the only two to eclipse the 40-mark. In 1960, Mantle was joined by all-timers Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks. The specialness of the club continued to grow, especially during years where just a single name would be in it. In 1965, Willie Mays stood alone in the club after mashing 52 long balls. Seven years later, in 1972, Johnny Bench resided above the rest when he hit 40 on the dot. The great Mike Schmidt would mimic Bench in 1983, clubbing 40 and doing so with no other players matching him.

When you stop and think about names like Ruth, Hornsby, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Williams, Mantle, Aaron, Banks, Mays, Bench, and Schmidt, these surnames ring with such high intensity, largely because of how talented each of them was in comparison to their field of counterparts. Followers of all sports, no matter the discipline, cling to superstars, and when there are just a few names that rise above the rest in a specific area that the enthusiasts find intriguing, these athletes become immortalized. Hence why the above players have a mythic-like feel associated with their titles.

Yet, in 1996, the trend of the 40-home-run club operating as a secret society, reserved for the best of the best, was thrown for a loop. A dramatic spike that, to this day, has yet to be duplicated. In the first full season since the disastrous strike, a record-setting 17 different individuals hit 40 or more home runs. For perspective, up until this point in time, there were only two seasons (1961, 1969) where at least seven players hit 40 home runs. Prior to 1996, the record was eight, which was achieved in the 1961 season, the same year that Maris hit 61. While there appeared to be something in the water during that year, that unique season of power was nothing compared to what took place in 1996.

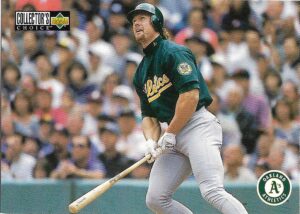

To spotlight the bunch, let us start from the top. Leading the American League in home runs was Mark McGwire, who, while suited up for the third-place Oakland Athletics, smashed 52. This production from Big Mac was of little surprise for fans of the sport who had followed his career. As a rookie, McGwire hit 49 dingers, which dwelled as the record for first-year players for quite some time. After his outstanding rookie season, McGwire went on to hit 40 or more in four of his next five seasons, including a year where he clubbed 42 in 1992. In 1995, he hit 39 in just 104 games, so when he passed the 50-marker a year later, it was somewhat expected. Though, to be frank, I do not believe anyone anticipated that he would need to play in just 130 contests to crack 50. Aside from clobbering more homers than everyone else, McGwire also led the league in at-bats per home run, as he went yard every 8.13 at-bats. At that time, it stood as the single-season record but eventually, as we will get to at a later point, was surpassed.

On the flip side, the man who finished a spot behind McGwire, Baltimore’s Brady Anderson, had a mere opposite track record to that of McGwire’s when it came to power hitting. After never hitting more than 21 home runs in a single year throughout his first ten years in the bigs, Brady Anderson hit 50 home runs, setting a new franchise record. Aside from etching his name atop a prestigious feat in the Orioles’ record book, Anderson also scribbled his name into the MLB history books. As the primary leadoff hitter for Baltimore, Anderson hit 12 leadoff home runs, the most ever for a player in the first spot of the order. In total, he hit 34 home runs from the leadoff spot, which had never been done before. Eleven of his 50 homers came in the month of April, which tied the record. During a four-game stretch (April 18-21), Anderson became the first player in MLB history to open a game with a homer in four consecutive contests, hitting one on the 18th, one on the 19th, a pair on the 20th, and another on the 21st.

With this insane boost in pop, the obvious question to ask was, where did this power surge come from? If you analyze Anderson’s minor-league statistics, you will find that he hit just 31 home runs in 1,185 at-bats. When he got the call up to the show, in his first 3,271 at-bats (1988-1995) he hit a total of 72 home runs. Quick math tells us that, when we combine his numbers, analyzing both his minor-league and major-league output, we find that Anderson was hitting a home run every 43.3 at-bats. In 1996, Anderson, en route to setting the new Orioles single-season record, went deep every 11.6 at-bats—a colossal contrast from the hitter he had been throughout his professional baseball journey.

Even without crunching the numbers, the average baseball fan who witnessed Anderson make history had their fair share of questions. As his home-run count grew higher and higher, some fanbases began expressing their speculations. During a series against the New York Yankees in the middle of September, fans of the Bronx Bombers, in unison, shouted “STER-OIDS! STER-OIDS!” directly at Anderson. As berating as it sounds, Anderson was not the first player to be accused by the fans of using performance-enhancing drugs. When Oakland’s Jose Canseco became the first player in baseball history to hit at least 40 home runs and steal 40 bases in the same season during his 1988 MVP-winning campaign, Thomas Boswell of The Washington Post inferred that Canseco had enhanced both his physical frame and power-hitting numbers due to the use of steroids (Boswell 23). Then, in 1989, fans began taunting Jose by giving him the same treatment on the ballfield that Anderson went on to endure years later. At that point in time, Boswell’s claim came in the absence of any hard proof, yet, like many topics in the story, there will be more to come on Canseco.

After his miraculous regular season, Anderson was quick to shut down anyone who was suspicious about his uptick in production. In October of that year, he was quoted in a Star Tribune article stating, “To understand what’s happened this year, you need to go back to when I was eight years old. . . . I’ve been working my whole life for this.” Anderson went on to note, “The improvement, I guess, comes from hundreds and hundreds of at-bats stretched over six months. Sometimes it doesn’t feel like I’m doing anything special, to be honest. It’s easiest for me if I try not to think about it and just show up every day and go to work” (Smith 15).

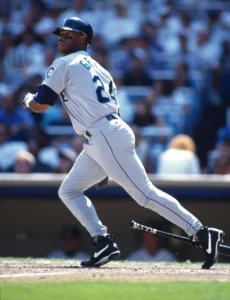

Finishing one home run shy of 50 was “The Kid,” Ken Griffey Jr. Unlike Anderson, Griffey’s 49 home runs, though his career high at the time, were anything but a surprise. At just 26, Griffey’s 1996 season marked the third time he had hit 40 or more home runs in his brief career. Far and away the most exciting player in the sport, it was the second straight year where Griffey was the American League’s top vote-getter for the All-Star Game, and the final tally was not close. Griffey finished more than 500,000 votes ahead of the next closest player, Cal Ripken Jr. Though, because of an injury he sustained on June 19 after fouling off a pitch, he was forced to sit out of the contest for the second year in a row.

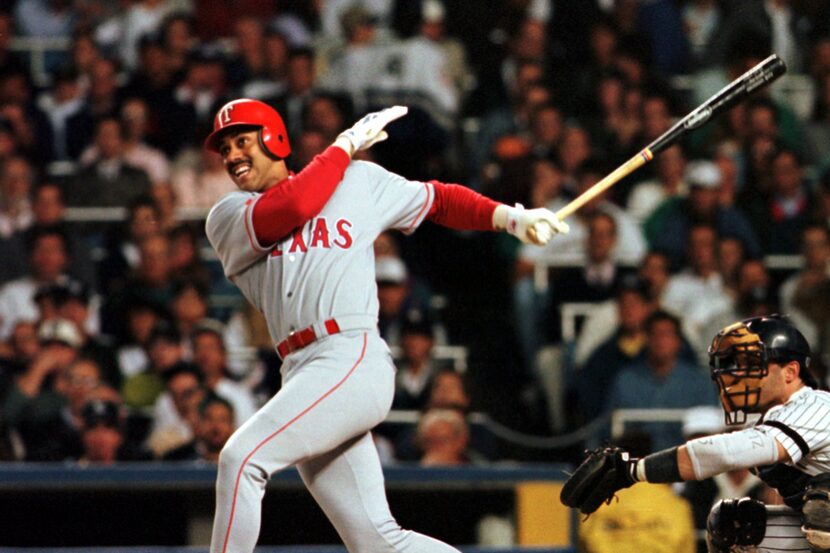

Another star who was no stranger to the 40-home-run club was the notorious Albert Belle, who clubbed a team-high 48 homers. Behind him was the National League’s leader in long balls, Colorado’s Andrés Galarraga, who mashed 47. Galarraga’s power hitting played a pivotal role in the Rockies finishing number one in the NL in attendance for the 1996 season, as not only did “Big Cat” lead the league in home runs, he also sat atop MLB in the RBI department with 150. Tied with the Rockies slugger in home runs was Juan Gonzalez of the Texas Rangers. Like Griffey, it was the third time Gonzalez had eclipsed the 40-mark. In honor of his efforts, Gonzalez was named the American League MVP. Due to his outstanding play, along with the aid of other key contributors in the Texas lineup, the Rangers made the postseason for the first time in franchise history.

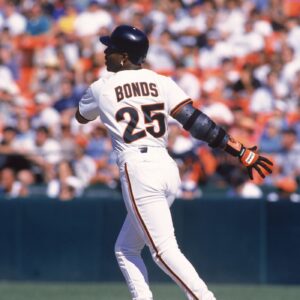

Rounding out the top ten in home runs were Griffey Jr.’s teammate Jay Buhner (44), the reigning AL MVP Mo Vaughn (44), Barry Bonds (42), and Florida’s Gary Sheffield (42). Among this select few, Bonds put together the most well-rounded season, stealing 40 bags to go along with his pop en route to becoming the second player in MLB history to post a 40-40 season. Even though his Giants were abysmal all year, as they had just one winning month (April) and finished last in their division with a 68-94 record, Bonds kept their games interesting by performing at a superhuman level. Though his team was in the cellar, Bonds, as an individual contributor, was so undeniably great that he still managed to lead the National League in votes for the All-Star Game.

A tick below Bonds and Sheffield was the New York Mets catcher Todd Hundley. Like Anderson, Hundley’s 41 home runs came out of left field, as the 27-year-old’s previous high was 16. Going into 1996, Hundley, across his first six seasons, was averaging a home run every 29.36 at-bats. In 1996, he went deep every 13.17 at-bats—more than two times better than his typical output. His 41 blasts were the second most by a catcher in MLB history, putting him right behind Johnny Bench, who clubbed 45 in 1970.

Akin to Hundley, 1996 was also the first year that Greg Vaughn, playing for both the Milwaukee Brewers and San Diego Padres, entered the 40-home-run club. Even though it was his first time reaching 40, Vaughn’s power was on par with how he had been slugging since joining the league. In 1991, he hit 27 home runs in 145 games, then followed that up with 23 dingers in 141 contests in 1992. He reached 30 the year after and put it all together in 1996.

Behind Vaughn were a pair of Galarraga’s teammates, Ellis Burks (40) and Vinny Castilla (40). For the second year in a row, Frank Thomas hit 40 on the dot, while Chicago Cubs outfielder Sammy Sosa (40) and the NL MVP winner, San Diego’s Ken Caminiti (40), each made their first appearance on the list. The latter, Caminiti, improved his AB/HR ratio dramatically. Prior to his MVP campaign, Caminiti, with a healthy sample size (3,967 at-bats), was hitting a home run every 39.2 at-bats. Miraculously, in 1996, he drove that number down to 13.65. After earning MVP honors, becoming the first player in Padres history to win the prestigious award, Caminiti said, “I got picked MVP for doing my job, basically. . . . I did my job to the best of my ability, and I got rewarded for it. I take my job seriously and I play as hard as I can play” (Johnson 12).

Works Cited

Boswell, Thomas. “Canseco’s Power: Natural or Enhanced?” The Washington Post, 15 Sept. 1988, p. 23.

Johnson, Mark. “Caminiti Reflects on MVP Season.” San Diego Union-Tribune, 18 Nov. 1996, p. 12.

Smith, Robert. “Anderson Addresses Power Surge.” Star Tribune, 5 Oct. 1996, p. 15.