After his preposterous stretch of dominance in the strike-shortened 1994 season, it appeared implausible for Greg Maddux to follow up his incredible campaign with an even more extraordinary run. Yet, somehow, the man whose introduction to baseball came at the age of four at a barnyard in Indiana where, if a ball was hit into the cornfield, it was considered a dinger, outdid himself. En route to winning his fourth straight Cy Young Award, Maddux led the league in wins (19), W-L percentage (.905), ERA (1.63), complete games (10), shutouts (3), innings pitched (209.2), and WHIP (0.811). On the road, he went a perfect 13-0, with a jaw-dropping 1.12 ERA. This unprecedented feat made him the first pitcher in history to win more than ten games on the opposition’s field without suffering a loss over the entirety of a single season. The man finished with more complete-game shutouts (3) than defeats (2). Just flat-out ridiculous.

To further put his outlandish season into perspective, Maddux became just the second player in the history of the sport to throw at least ten complete games, with an ERA lower than 1.75, and a win-loss percentage above .900. In order to find the first and lone other hurler to do this, one would have to turn the clock back 120 years, to 1875. 1875 is the year that Alexander Graham Bell was recognized as the inventor of the telephone. It was also the year that the Civil Rights Act was passed and the first Kentucky Derby took place. On the diamond, a 24-year-old pitcher named Al Spalding had a year for the ages while playing for the Boston Red Stockings in the National Association.

Competing on a team with only a few players who were able to pitch, Spalding started 62 of the Red Stockings’ 82 contests, while coming on in relief for another ten appearances. In total, Spalding pitched in 87.8% of the games. In alignment with today’s 162-game schedule, that would be the equivalent of a player appearing in 142 ballgames. Quite obviously, the game was much different in the late 1800s, but no matter what, pitching in almost every contest over the course of a season is an achievement, regardless of velocity, playing conditions, opposing skill level, or intent behind the location of each toss.

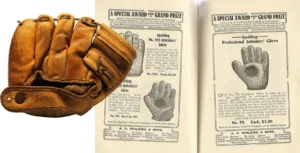

Over 570.2 innings of work in 1875, Spalding went 54-5, with a 1.59 ERA. He threw 52 complete games and led the league with seven shutouts. If you saw the name “Spalding” and immediately wondered if there was a correlation between him and the notable sports equipment manufacturing company with the same surname, then you are thinking on the right track. Albert Goodwill Spalding, the standout pitcher who served as both an executive and manager in the sport of baseball, is the same Albert Goodwill Spalding who co-founded the sporting goods company. To give you an understanding of how his business came about, let us wind the clock even further back into the past. For the first thirty years of its existence, baseball was played as a barehanded game. During this stretch, since it was all they knew, the ballplayers had no issue with their lack of protection. Yet, over time, as they underwent more wear and tear, a few of them decided to start shielding their hands with some sort of protection, to which they were scorned by the others who were tough enough to play barehanded. If a player was seen with any type of hand protector, they were considered “soft” and “sissy-like.” For that reason, those who did opt to safeguard their metacarpus did so as discreetly as possible. These outliers would put on a skin-tight, borderline-imperceptible palm glove that was fingerless, which made it even harder to see with the naked eye. It was not until around 1891 that any sort of manufactured mitt was padded, so even though these players took it upon themselves to protect their hands, they were not totally defending their palms from the ball. Yet, the move was still frowned upon.

Even though it was perceived as a coward-like decision, as the game evolved, so too did the collective desire to guard the hands. In the late 1860s, those who played both catcher and first base—the two positions on the field that get the most balls thrown to them over the course of a standard contest—would routinely finish games with bruised palms as red as Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer’s muzzle. So, as expected, players who played these spots were the first to use gloves. Much like the origin of the telephone is up in the air, as some believe that it was an Italian immigrant named Antonio Meucci, not Bell, who invented the device, there are conflicting stories on the diamond over who was the first to be seen sporting a glove on a consistent basis. Though unsupported with any sufficient evidence, some believe that catcher Doug Allison of the original Cincinnati Red Stockings had a saddlemaker fabricate him a mitt so that he could use it while catching for the first professional baseball team in 1869. Though Spalding denies ever seeing Allison with a glove. His first recollection of a player using a mitt came years later in 1875, when he saw New Haven first baseman Charles Waite sporting a slender, fresh-dyed glove on his fielding hand. Though it lacked any sort of padding and was concealed by design, it is said that Waite was embarrassed to wear it. If a fan, a player from the opposing team, or even one of his teammates saw that he was using protection, he would get berated for being a “sissy.” Keep in mind that if Waite was the first person that Spalding saw wear a mitt, that means, in his incredible 1875 season, the pitcher was gloveless, which goes to show how ridiculous of a season Maddux had in 1995.

Though, at the beginning, players like Waite were the butt of the joke for not being tough enough to catch the ball with their bare hands, the energy shifted a few years later when Spalding, a very much respected ballplayer amongst his peers, decided to employ a glove. The moment he saw Waite with one on, instead of scolding him with hate, Spalding assaulted him with an army of questions about its makeup. While he was fascinated with it, the hurler, due to the pestering that Waite received for playing with such “girlish” protection, waited two more years before he started wearing one.

Since he was so admired, when Spalding began wearing a glove in 1877 while playing first base, as he had just retired from pitching, no one mocked the baseball icon. What is interesting is that Spalding sported a black-colored glove, one that, by design, approximates well with a modern-day golf glove. This showed that he possessed little to no care in trying to hide what he was wearing. The consensus was that, if Spalding, the best pitcher of his era, thought it was cool to wear a glove, then it was now cool to rock one. Sparking a trend, Spalding’s decision to use a mitt turned the glove into a ubiquitous object on the field of play. Bat and ball, the two main entities in the sport, adopted a brother, which was the glove. Due to Spalding’s influence, players from all around the league picked up a mitt, akin to the icon’s in its nature, for anywhere between $1 and $2.50. To add extra protection, a small portion of players wore a glove on each hand while competing—a niche fad that soon went out of style as the product evolved. The original gloves were constituted from cowhide, horsehide, or “Indian tanned” buckskin. Up until the 1930s, the bulk of manufactured mitts were made from horsehide, before cowhide took over as the primary element.

As the majority of players in the late 1870s followed in Spalding’s footsteps, by 1895, the “glove” had made its way into the sport’s official rule book: “The catcher or first baseman are permitted to wear a glove or mit (the word ‘mitt’ was often spelled with just one ‘t’ at the time of the publication) of any size, shape, or weight. All other players are restricted to the use of a glove or mit weighing not over ten ounces and measuring in circumference around the palm of the hand, not over fourteen inches” (Official Baseball Rules 1895).

All this to say, to find a true comparison to Greg Maddux’s 1995 season, one that, from a statistics standpoint, lines up with The Professor, you have to refer to a player in the nineteenth century who popularized the glove.

Works Cited

Official Baseball Rules 1895. National Association, 1895.